An elite unit of household guards in the Byzantine Empire between the ninth and fourteenth centuries.

In the latter part of the tenth century, the Byzantine emperor Basil II recruited a number of Varangians, reputedly Norse- men from Russia, as a personal bodyguard. The term Varangian comes from the Norse var, meaning “pledge,” and denotes one of band of men who pledged themselves to work together for profit. Usually this meant in trade, but the oath of loyalty to each other certainly had more than commercial meaning, for they were bound to fight for each other’s safety as members of merchant band. The term also refers to men who hired themselves into the service of an overlord for a set period of time, as the Norsemen did for the lords of Novgorod and Kiev in Russia. Thus, the term Varangian does not necessarily mean “Viking” or “Scandinavian,” although most of them were from that part of the world. Generally, however, it refers to the Scandinavian Russian Empire led by the city states of Kiev and Novgorod.

Varangians fought southward down the Volga toward territory under Byzantine control, raiding the area around Constantinople in 865. As the Byzantine emperors fought to protect their northern frontiers, they gained firsthand knowledge of the fighting abilities of these men. In 911 Prince Oleg of Russia concluded a trade agreement with Constantinople, and it was through these more peaceful contacts that Emperor Basil II began to hire Varangians for his personal guard, starting an organization that lasted until at least the 1300s. Basil made use of his new soldiers immediately, taking them with him on an expedition into Bulgaria, where the Varangians so distinguished themselves that Basil separated them from the remainder of the army in order to give them a larger share of the loot. They also served under his command in Anatolia and Georgia, continuing to fight ferociously and earn the emperor’s respect. In the Balkans, the Varangians fought one of the most determined of Byzantine foes, the Pechenegs. The Pechenegs’ defeat led to a peace treaty with Constantinople in 1055. After another defeat at Varangian hands in 1122, they served the emperor’s army as light cavalry.

Although the Varangians served in the army that fought in Byzantine campaigns, their service as a palace guard was most important to the various emperors. They had three main functions. First, they guarded the safety of the emperor, standing at the entrance to his bedchamber and in the reception hall. Second, they occasionally were known to have guarded the imperial treasury, over the funds of which they apparently thought they exercised some control. Third, late in their tenure, they acted as prison guards and probably as torturers.

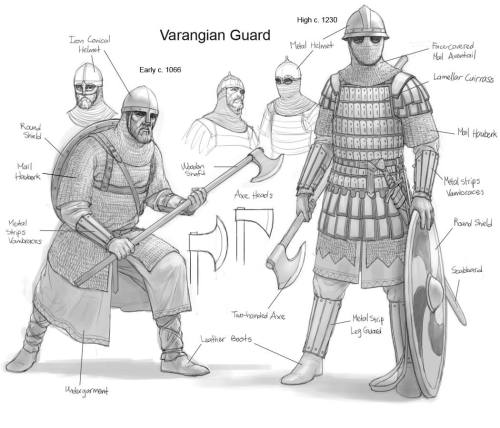

The Varangian Guard was best known for its weaponry, for they carried axes, sometimes described as single-bladed and sometimes as double. “The imperial axe-bearers” is a common description of them. The Varangian Guard’s top commanders seem to have been Byzantine, although smaller units had foreign commanders. By the later stages of their service, larger numbers of Anglo-Saxons, especially from England, entered the Guard. One source refers to an “axe-bearing Keltikon,” and Celt seems to have become a standard description of the Guard members by the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, especially after the capture of England by William the Conqueror. Icelandic sagas tell of their natives serving in the Guard as well.

The primary characteristic of Guard members, apparently, was their loyalty. The Byzantine Empire was a virtual breeding ground of intrigue, and the emperors seemed always to be under threat of overthrow or assassination. By hiring foreign troops and paying them very well, the rulers hoped to avoid the problems of subversion and infiltration by local political factions. This was a successful strategy, but often put the Varangians themselves in difficulty. The generally accepted view of overthrow and assassination in the Byzantine Empire was a variation on the Chinese concept of the “Mandate of Heaven.” If an individual came to the throne, it was through God’s will. If he was removed, violently or otherwise, that was also God’s will. Thus, the Varangians had to accept an ever-changing political situation and be prepared to fight to the death for one emperor but immediately support his successor against whom they may have fought hours earlier. The record of the lavish gifts and bonuses given to the Varangian Guard upon the succession of a new emperor shows the Guard’s ability to adapt to, and indeed profit from, this power shift.

The best known of the Varangians was Harald Sigurdson, also known as Harald Hardraada, who served in Constantinople as a young man before returning to his homeland and leading forces defeated by King Harold of England at Stamford Bridge in 1066. Harald fled his homeland at age 15 after his family, the ruling power of Norway, was defeated in battle. He served in the military in Russia, where he seems to have fallen in love with the daughter of an aristocrat, Yaroslav. She apparently was in the royal court in Constantinople, and he followed her there. Yaroslav wanted more than royal blood for his son-in-law, so he bade Harald make a name for himself before he could have the daughter’s hand in marriage. Harald arrived in Constantinople in 1034 and entered into the service of the newly crowned Emperor Michael IV. The Icelandic saga penned by Snorri Sturluson tells Harald’s tale and describes him as an outstanding military leader, determined and clever, and always able to end a battle with much plunder. Contemporary accounts written by Byzantine observers confirm his abilities in campaigns in Sicily and Bulgaria.

After the Byzantine defeat at the hands of the Turks at Manzikert in 1071, the Byzantine army became even more dependent on mercenaries, and the Varangians served as the loyal core of the military. They were not always victorious, however. By 1082, the Guard was becoming increasingly Anglo-Saxon, and it was the descendants of the Norsemen, the Normans of France, who ironically were the instrument of a Guard disaster. The great Norman leader Robert Guiscard aspired to become the Byzantine emperor, so he led his forces out of Sicily across the Adriatic Sea. He laid siege to the city of Durazzo on the island of Corfu in 1081 but was forced to lift the siege upon the arrival of the Byzantine emperor, Alexius Comnenus, with 50,000 men. The Varangian Guard, some of whose members had fought the Normans at Hastings in 1066, couldn’t wait for the bulk of the army to position itself. They flung themselves at the Nor man position and succeeded in forcing a hasty retreat, but their pause to plunder the Norman base gave their enemy time to regroup and counterattack. Surrounded, the Guard fought to the last man.

The Guard also distinguished itself in a losing effort in 1204 when the Fourth Crusade attacked Constantinople instead of Muslim targets further inland. The Varangians defended the walls of the city for two days until Venetian ships flung incendiaries over the walls and set the city afire. In the ensuing melee, the Varangian Guard was virtually wiped out. The final references to Varangians in Constantinople occur in 1395 and 1400, when some appeared to have been serving in administrative, rather than military, capacities in the Byzantine government.

References: Bartusis, Mark C., The Late Byzantine Army (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992; Davidson, H. R. Ellis, The Viking Road to Byzantium (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1976).