Dominant military forces of the Middle East between the fourth and fifteenth centuries.

At Manzikert 26 August 1071, the Seljuk Turks led by Alp Arslan defeated the Byzantine Empire. The brunt of the battle was borne by the professional soldiers from the eastern and western tagmata, as large numbers of the mercenaries and Anatolian levies fled early and survived the battle. The fallout from Manzikert was disastrous for the Byzantines, resulting in civil conflicts and an economic crisis that severely weakened the Byzantine Empire’s ability to adequately defend its borders. This led to the mass movement of Turks into central Anatolia; by 1080, an area of 78,000 square kilometres (30,000 sq mi) had been gained by the Seljuk Turks. It took three decades of internal strife before Alexios I Komnenos (1081 to 1118) restored stability to the Byzantines. Historian Thomas Asbridge says: “In 1071, the Seljuqs crushed an imperial army at the Battle of Manzikert (in eastern Asia Minor), and though historians no longer consider this to have been an utterly cataclysmic reversal for the Greeks, it still was a stinging setback.”

In 330 ce, Constantine I, Emperor of the Romans, founded a new capital for his empire on the triangular peninsula of land that divided the Bosphorus from the Sea of Marmara, commanding the narrow water passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. He named it Constantinople, and in time it grew to be not only one of the greatest cities of antiquity, but the center of one of the most impressive civilizations the world has ever seen: the Byzantine Empire.

Within 200 years, the Byzantines (or Eastern Roman Empire, as they styled themselves) had grown to massive proportions, controlling all of Italy, the Balkans, Greece, Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, and Southern Spain. Such an empire could be held together only by a strong and efficient military, and for several centuries the Byzantine army had no equal anywhere in the world.

Although the empire had expanded enormously through conquest, the basic role of the Byzantine army was defensive. Fortifying the long borders was out of the question, and since raiders and invaders could strike anywhere along the empire’s frontier, the army needed to be able to move quickly to meet these threats. Like their predecessors, the Roman legions, the Byzantine units formed a professional standing army which was trained to near-perfection as a fighting machine. Unlike the legions, however, the core of the army was cavalry and fast-moving foot archers. Speed and firepower had become the trademarks of the “new Romans.”

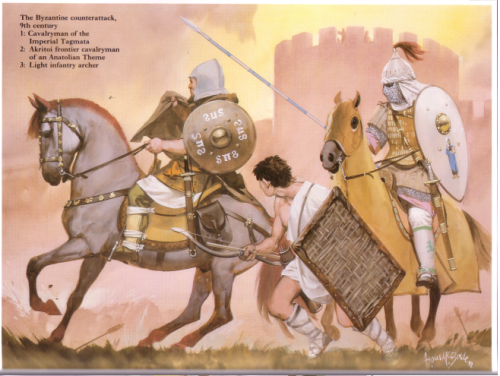

The stirrup reached the empire from China early in the fifth century, and increased the effectiveness of the cavalry enormously. Therefore, the core of the Byzantine army became the heavy cavalry. A typical heavy cavalryman was armed with a long lance, a short bow, a small axe, broadsword, a dagger, and a small shield. He wore a steel helmet, a plate mail corselet that reached from neck to thigh, leather gauntlets, and high boots. His horse’s head and breast might be protected with light armor as well. By the later empire, armor for both rider and horse became almost complete, especially in the frontline units. In a secondary role, unarmored light cavalry horse archers on smaller mounts supported the heavy units with missile fire, while other light cavalry armed with a long lance and large shield protected their flanks.

The infantryman who usually accompanied the cavalry in the field was either a lightly armored archer who used a powerful long bow, a small shield, and a light axe, or an unarmored skirmisher armed with javelins and shield. Because most Byzantine operations depended on speed, tactically as well as strategically, heavy infantry seldom ventured beyond the camps or fortifications. The heavy infantryman wore a long mail coat and steel helmet and carried a large, round shield. He used a long spear and a short sword. The Varangian Guard, the emperor’s personal body guards, were famous for their great two handed axes which they wielded with great effect. Their armor was almost complete plate and mail from head to foot.

To the Byzantines, war was a science, and brains were prized over daring or strength. Military manuals such as the Strategikon (ca. 580) and the Tactica (ca. 900) laid down the basics of military strategy that really did not vary for almost a thousand years. The army was always small in number (field armies almost never exceeded 20,000 men, and the total force of the empire probably was never greater than 100,000) and, because of its training and equipment, very expensive to maintain. Huge losses in combat could be catastrophic, and seldom were great winner take-all battles fought. The goal of any Byzantine general was to win with the least cost. If by delay, skirmishing, or with drawing the local population and their goods into forts he could wear out an invading force and cause it to withdraw without a costly pitched battle, so much the better. Bribing an enemy to go away was also quite acceptable.

The warrior emperor Heraclius divided the empire into some 30 themes, or military districts, each under a separate military commander. Each theme provided and supported its own corps of cavalry and infantry, raised from self-supporting peasant warrior-farmers, enough to provide a small self-contained army that was capable of independent operation. For four centuries this system endured, and Byzantium remained strong. Only in the eleventh century, when the theme system and its free peasantry were abandoned, did the empire become weak and vulnerable.

Because theme commanders depended on accurate information about enemies and their movements, they maintained a very sophisticated intelligence service. Over time, espionage became so important to Byzantine operations that a part of the emperor’s bureaucracy, known as the Office of Barbarians, was dedicated solely to gathering military intelligence and disseminating it to the commanders in the field.

Byzantine battlefield tactics, although highly flexible and adaptable, were based invariably on archery first, then shock assault as needed. Since everyone in the army except the heavy infantry carried a bow, an incredible amount of firepower could be directed against the enemy. The highly trained and disciplined cavalry units, supported by the light infantry archers, could pour volley after volley of arrows into enemy units and then, when those units began to lose cohesion, charge with lance and sword, rout them, and pursue them out of Byzantine territory.

Since Constantinople was a major port, surrounded by water on three sides, a strong navy was also necessary for the empire’s survival. Byzantine ships were fairly typical oar-driven galleys of the time, but they possessed a great technological advantage over other navies: a weapon known as Greek fire. This was a highly flammable mixture that could be thrown on enemy ships in pots from catapults, or pumped by siphons directly on their decks, breaking into white-hot flames on contact. If water was poured on Greek fire, it burned even hotter. One of the great secrets of the ancient world is the exact composition of Greek fire, but it probably contained pitch, kerosene, sulfur, resin, naphtha, and quicklime. Whatever the mix, it was a terrifying weapon that was almost impossible to defend against. With Greek fire, the Byzantine navy reigned supreme for centuries on the Black Sea and the eastern Mediterranean.

The Byzantines were also fortunate in producing many great military leaders over the centuries: emperors such as Justinian I, Heraclius, Basil I, Leo III, Maurice, Leo VI “the Wise,” and generals like Narses, Belisarius, and John Kurkuas. Their skills and insights maintained the Eastern Roman Empire for almost a thousand years after the fall of the western branch.

Although the Byzantines fought many peoples over the centuries, in campaigns of either conquest or defense, it was a religious opponent, the Muslims, who became their most intractable, and in the end, lethal, foe. For seven centuries, a succession of Muslim generals led Persian, Arab, and Turkish armies against the armies and walls of Constantinople. Gradually, the empire was eaten away, and its wealth and manpower base eroded. Not only did the Byzantines have to face the Muslim threat, but a growing schism between their church, the Greek Orthodox, and the Roman Catholic Church, isolated them from their fellow Christians. In 1071, the emperor Romanus IV violated one of the mainstays of Byzantine strategy when he concentrated most of his military power in one great battle against Alp Arslan and the Seljuk Turks at Manzikert in Armenia. The result was a devastating defeat, allowing the Turks to overrun most of Asia Minor, the heartland of the empire. Byzantium never really recovered from this debacle. In 1204, Christian crusaders, allied with the city-state of Venice, took advantage of internal Byzantine strife to seize and sack Constantinople. It was not until 1261 that the emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus recaptured Constantinople from the Latins, but the damage had been done. The empire’s once great resources, and its ability to maintain itself, were almost gone. On May 29, 1453, Mohammed II, Sultan of the Ottoman Turks, using great cannons (weapons even more fearsome than Greek fire), broke through the seemingly eternal walls of Constantinople and brought the glorious Byzantine Empire to an end.

Certainly, Byzantines made many great contributions to civilization: Greek language and learning were preserved, the Roman imperial system and law was continued, the Greek Orthodox Church spread Christianity among many peoples, and a splendid new religious art form was created. But it is possible that their ideas on military science (mobility and firepower; delay and deception; espionage and state- craft; an emphasis on professionalism over the warrior ethos) might stand as the most significant aspect of their great legacy.

References: Diehl, Charles, Byzantium: Greatness and Decline (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957); Griess, Thomas, Ancient and Medieval Warfare (West Point: U. S. Military Academy, 1984); Ostrogorsky, George, History of the Byzantine State (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957).