The greatest concentration of white settlers lived around the city of Peking, where they could interact more freely with the great population there as well as with the imperial government. Apart from traders and missionaries, Peking was also home to the diplomats of foreign powers. These government representatives lived together in a single area of the city where their legations were located. There were eleven such legations: British, American, Japanese, German, French, Austrian, Russian, Spanish, Belgian, Dutch and Italian. The ministers, their official staff and all of their families felt increasingly threatened by the Boxers, and this fear was communicated to the outside world. The fanatical cult that had originated in Shantung had spread slowly over the months from village to village until it had reached the province of Chihli, at the centre of which was Peking. By the last week of May in 1900, the Fists of Righteous Harmony had reached the many gates of the imperial city.

The empress dowager’s foreign office, the Tsungli Yamen, did little to protect the legations from danger, promising armed guards but not providing them in adequate numbers. Rather than have to depend on unreliable Chinese protection, the foreign powers began building up a small garrison of soldiers, much to the displeasure of the anti-foreign faction of the Chinese government. In addition, the allied naval fleet that was anchored at the mouth of the Pei Ho River in the Gulf of Chihli decided, after some prevarication, to send reinforcements to Peking. This 2,000-strong expedition was commanded by Admiral Seymour, and it Left on 10 June by train. The first leg of the journey took it to the port of Tientsin, and .is it rolled further north it had to garrison stations and settlements so as not to have its line of retreat cut off. But at Tang T’su, on the way to the capital, this was exactly what happened. Boxers made several fanatical attacks on the trains and succeeded in isolating the expedition by destroying rails, bridges and water-tanks. During their attacks the Boxers cut the throats of their wounded, hoping to deny the allies any prisoners. What had set off as a relief force now found itself faced with the prospect of having to fight its way back to Tientsin through Boxer-infested country. It eventually retreated southwards along the Pei Ho River and reached Tientsin by 26 June. During the desperate retreat of the expedition, the allied fleet at the Taku Bar at the mouth of the river moved to attack the imposing Taku forts which guarded access to the river and could prevent the fleet moving upstream to Tientsin. Nine ships of the fleet approached the forts and, when their ultimatum to the Taku forts to surrender had almost expired, came under fire. Landing parties were able to take the Taku forts by 17 June, but the empress had managed to learn of the fighting there and mistakenly assumed that the victory was a Chinese one. Flushed with false success, she declared the whole of China at war with the foreign powers and summoned the Chinese army to join with the Boxers. China’s Grand Army of the North was ordered to enter the legation area of Peking and slaughter every European it found, but the tough defenders were able to put up stout resistance.

Peking was experiencing panic: there were lootings, fires and other disturbances, murders were carried out on the streets, and several times guards from the barricaded legation quarter entered the streets to rescue endangered Christians. On 20 June the German minister, Klemens Graf von Kettler, was murdered on the streets of the imperial capital by a Chinese army corporal. Soon after this disturbing event, a mob of Boxer fanatics attacked the Austrian legation, but they were driven back by machine-gun fire. Trenches were hastily dug and barricades were built; the legation was now under siege. The tiny allied force within the confines of the legation area was hard-pressed, and it used ingenuity and skill in defending the other Europeans. Peking was now totally isolated from the rest of China, the allied fleet, the Seymour expedition and the allied garrison at Tientsin, which itself had come under attack from Boxer cult members. Everywhere Europeans and Christians were being attacked by the cult and now also by the Chinese army.

The foreigners at the port of Tientsin had to defend a five-mile perimeter from the massed attacks of the fanatics and the soldiers. All kinds of merchandise were employed as material for barricades, including expensive bales of silk! A courageous mining engineer called Herbert Hoover was able to help in the construction of Tientsin’s defences; this man would later become president of the United States. Being so close to the fleet off Taku, those besieged at Tientsin were the first to be relieved by the timely arrival of an allied army on 23 July. Once Tientsin had been secured, more troops were assembled in the shattered city for a second attempt to reach Peking and the foreign legations, from where no word had come since the beginning of June. No one knew whether the besieged were dead or still struggling valiantly against the Boxers. When the multinational force had collected, it began the journey to Peking on 4 August. Following the line of the river and the railway inland, it encountered pockets of Chinese resistance, usually from rogue elements of the army, since the Boxer cult members were now becoming a rarity. Either they were low in numbers from their fanatical attacks on allied positions or they were abandoning their cause to fade back into the population. From the start of August, the Boxers no longer feature in the uprising as a credible military force, but only as lone murderers and criminals to be hunted down.

In Peking the different foreign legations had pulled together in this desperate struggle for survival, sharing food and water and combining their tiny troop numbers in an attempt to defend the legation area. The head of the British legation, Sir Claude MacDonald, led the defence of the 3,000 civilians with only 389 men, seventy-five volunteers and twenty officers. By far the greatest military asset the legations possessed was Colonel Goro Shiba. Both the colonel and his twenty-five Japanese soldiers fought valiantly against a far greater number of Boxers and Chinese troops. All knew that a single lapse in the defence would bring about the certain death of everyone within the legation area, and this tense drama was the source of much heroism, tinged as it was by the lack of any information whatsoever about the state of the allies elsewhere. Had they fled China? Was a relief column just outside of the city? Did anyone know they were still alive? The siege of Peking was to last an agonizing fifty-five days.

The empress dowager and her close advisers within the Forbidden City palace complex at the heart of Peking had grown alarmed by the reports of the allied victory at Tientsin and so the Tsungli Yamen reestablished contact with the beleaguered legations. Their tone was now one of desperation, and the legations were repeatedly offered safe passage to Tientsin. Guardedly, they declined to attempt the hazardous journey, fearing a trap. Further half-hearted attempts were made to resolve the awful siege. Flags of truce appeared one day, to enable the Chinese to bury their dead, who littered the streets surrounding the legations. Sir Claude Mai Donald even met with our of the Chinese chiefs during another truce, and Further communications resulted in a cart of fresh fruit being delivered to the thirsty and hungry defenders. But these sporadic overtures often ended as quickly as they had begun, the empress dowager being swayed sometimes by the moderate influence of Prince Ch’ing and at other times by the hardline anti-foreigner Prince Tuan.

One can imagine an old woman who, having placed her faith in the sinister forces of a secret cult, was forced to listen in shocked amazement to reports of the Boxers being cut down by gunfire just as easily as mortal men. Her hopes of expelling the ‘foreign devils’ by supernatural means had been dashed and she was now tentatively looking for some way to resolve the dangerous situation. The international consequences of annihilating the legations were too horrible to contemplate, and with well-trained and well-armed troops on their way to lay siege to Peking, some kind of compromise was necessary. Her army had modern rifles, a stock of machine-guns (which remained in their packing crates) and the massed manpower to easily overcome the legation defences in just a few concerted assaults. But still the siege dragged on.

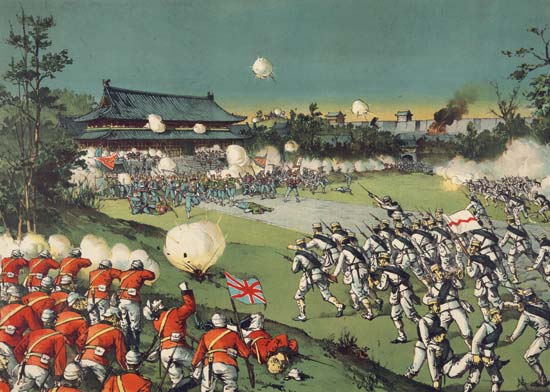

Following a large battle to the south of Peking with government troops on 5 and 6 August, the international relief force marched on the city. It had already lost considerable numbers of men as battle casualties and, since they were low on water and blistered by heat, the severe hardships of the march had taken their toll. The polyglot army, including Russians, Japanese, French, Americans and British (mainly Indian levies), prepared to attack Peking, relieve the legations (if anyone were left alive there) and depose the empress dowager in the Forbidden City. As the armies assembled for the agreed start of the attack, it soon became clear that the Russians had sent in an advance party that had not only prematurely moved against Peking but also cut diagonally across the battlefield to attack the American objective, one of the massive gates. Whether the Russians had sent just a scouting party or actually desired the glory of breaching Peking’s walls first is not known, but the planned assault on the city was abandoned and all of the armies moved into battle immediately. This combined effort, with each army charged with seizing different objectives, managed to throw back the Chinese defenders, and on the afternoon of 14 August the legations were relieved.

Little more than a mile from the legations stood the imposing edifice of the P’ei Tang Cathedral, which had been under siege for as long as the legations but was somehow overlooked during that first frantic day of liberation . . . and on the second. On 16 August a small force was dispatched to take the cathedral. In the tiny compound were 3,000 Chinese converts in desperate circumstances. They had suffered the horrors of Boxer raids and highly destructive mines that had been exploded underneath the compound. The defenders knew little of what was happening elsewhere, and the brave scouts that the forty French and Italian marines dispatched never returned, their heads and carefully flayed skins being displayed on poles by the Boxers. After an abortive assault on the main gates of the Forbidden City by the American contingent, Pe’i Tang Cathedral was eventually secured.

Ironically, during the cathedral’s reconstruction by Chinese labourers following the siege, Bishop Favier was certain that most of the coolies had been active participants in the Boxer cult and were responsible for many of the horrors that he had witnessed during the days of the siege. But the bishop held no grudge. The first the defenders had seen of Boxer cult members was on 15 June, when a party of Boxers, all clad in red, assembled near the Pe’i Tang’s south entrance. With ritual movements and magical signs, they began to advance on the cathedral slowly and ominously, brandishing burning torches and swords. The cultists then knelt to pray and, as they did so, the defenders opened fire on them, forcing them to flee. Nothing could stop the allied armies now from despoiling Peking and taking their revenge on the Chinese who had caused all of them so much suffering. On 28 August the Imperial Palace within the Forbidden City was taken and during the following months the Russians occupied parts of Manchuria in northern China, while the German troops, led by Field-Marshal Waldersee, conducted sadistic and brutal revenge attacks on the peasantry around the capital. The empress dowager herself had fled after the fall of Peking, but she negotiated a surrender from the regional city of Sian on 26 December 1900. There was little that she could do now to prevent the foreign powers from taking whatever they desired and imposing upon the Chinese people and its government any measure, however unfair. In September 1901 the Boxer Protocol was signed, guaranteeing to the foreign powers very substantial reparations for the folly of the empress dowager’s political adventure.

Old and wily, and a survivor until the end, the empress dowager died in mysterious circumstances on 15 November 1908, the day after the death of Emperor Kuang-Hsu himself. These two deaths are still unexplained, and highly suspicious, but they paved the way for the accession to the Manchu throne of the last emperor, two-year-old P’u-i, who reigned as Emperor Hsuan-t’ung until the revolution of 1911 brought to an end over 2,000 years of imperial rule.