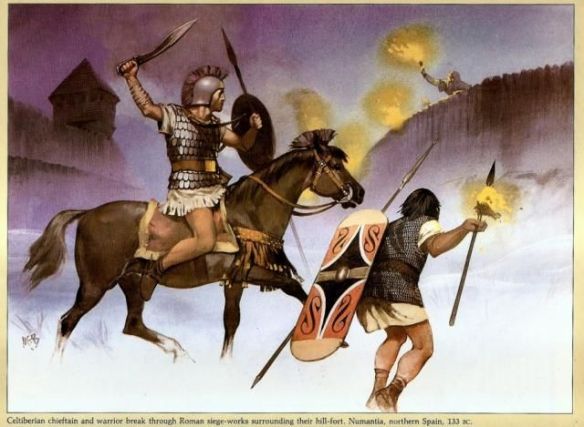

Numantia (Celtiberian) finally falls in 133 to Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus

Date: 134–133 b.c.

Location: on the Duero River, near present-day Soria in northeastern Spain.

Forces Engaged:

Roman: 60,000 legionnaires. Commander: Scipio Aemilianus.

Celtiberian: 4,000 troops. Commander: Avarus.

Importance:

The fall of Numantia marked the end of organized Celtic resistance to the Roman occupation of Spain.

Historical Setting

The Roman Republic first showed an interest in Iberia in the wake of the First Punic War. Iberia had long been the major source of mercenaries for the Carthaginian army, as well as a source of natural resources. For a time Carthage controlled the southern part of the peninsula and Rome the upper part near the Pyrennees. The Second Punic War began over a border dispute in Iberia, and in the wake of Rome’s victory at Zama all of Iberia fell under Roman sway. Unfortunately, the inhabitants, a mixture of Celts and local populations, were fiercely independent and resisted Roman rule at every turn.

The First Celitiberian War was fought in the years 181–178 b.c. Roman forces under the leadership of Tiberius Gracchus subdued many of the tribes, and he developed a reputation for fairness in dealing with his defeated enemies. Until 155 the region remained fairly peaceful, as the Romans consolidated their hold on the coastal regions and the interior tribes recovered from the war. In 154 the Lusitani (of modern Portugal) attacked Roman territory but in 151 they were defeated by the Roman Sulipicius Galba. He offered them terms of surrender that they accepted; he then slaughtered 8,000 men who had given up their weapons. This act of treachery was unfortunately not uncommon, for most officials sent to Spain had little desire to be there and faithlessness in their dealing with the Celtiberians was a regular practice.

Along with the Lusitanian uprising, the Aravaci tribe of northeastern Iberia also made war against the Romans. They joined with the Lusitanian leader Viriathus and for a few years made life miserable for successive Roman officials, until the consul Q. Serivlius Caepio bribed two of Viriathus’ officers to assassinate him in 139. The Aravaci continued their resistance after Viriathus’ death. Their main city was Numantia, on the Duero River. When the Third Celt- iberian War broke out in 143, the Romans attempted to reduce Numantia by siege. Because the city was located on steep bluffs overlooking the river and garrisoned by aggressive warriors, the Romans had no luck. Quintus Pompeius Metellus was the first to try in 143, and all he could achieve was an agreement to leave the city independent. He violated that agreement in 139, and the Numantines appealed to the Roman Senate for justice. They got none. Pompeius was removed and replaced by Marcus Popilius Lenatis. He made no headway against the city either, so was succeeded by Caius Hostlius Mancinus, who ordered a number of assaults on the city, all of which were repulsed. His army was ambushed and he was obliged to sign a treaty very favorable to the Numantines.

The Senate in Rome rejected that treaty and in 136 another commander tried to take the city, then another in 135. Increasingly dissatisfied with the progress in Iberia, the Senate finally gave in to public demand to reappoint Scipio Aemilianus Africanus to the consulship. He was the victor over the Carthaginians in the Third Punic War and captor of the city of Carthage itself in 146. If anyone could overcome the strong defenses of Numantia, he would be the man.

Scipio was indeed the man for the job, but he had obstacles to overcome before he confronted Numantia. The army’s morale was extremely low, and getting recruits to go to Iberia was difficult. The Celtiberian guerrilla tactics frustrated most Roman soldiers, so veterans had little desire to reenlist. As the countryside had been fought over continuously for decades, and the population was tribal rather than urban, potential recruits could not be lured by the promise of plunder, for almost none existed. Scipio had to raise an army on his reputation, and he managed to amass a force of 20,000 Romans. This was expanded by a further 40,000 allies and mercenaries, mainly locally recruited but also including cavalry from Numidia in North Africa.

Scipio’s first task was to whip his army into shape. He drove his new recruits and the troops he inherited upon his arrival in Iberia, making them march, dig in, and then march some more. He hardened their bodies and their spirits, and occasional skirmishes with Iberian tribes enhanced their morale while decreasing that of the locals. In the fall of 134 he was ready. He marched to Numantia and began encircling it. Knowing the Numantines’ vaunted aggressiveness, he decided to neutralize their fighting spirit by not letting them fight. He would not storm the city, but lock it up and starve it out.

The Siege

Scipio established two camps immediately upon his arrival at Numantia, and over the course of the siege he set up five more. Between the camps he built a wall, ultimately with seven towers interspersed along it. The walls were 10 feet high, and from the towers Roman archers and slingers could hit targets within the city. Where the Romans could not build a wall because of a swamp, Scipio had a dam constructed to back up the water flow, which created a lake between his walls and those of Numantia. The Duero, which had protected the city, now encircled it. At the river’s entry and exit points Scipio had towers constructed on both banks, between which was strung a cable. Dangling from the cable were beams with sharp blades embedded in them, hanging into the water, to block both boats and swimmers. The Numantines were well known for their ability to swim the river, but now their only points of egress were blocked. Further, Scipio had his men build walls of contravallation, to defend against any relief force.

The defenders grew increasingly hungry and frustrated with the inaction. Only once did they attempt a sally, and it was easily repulsed. One of the leading Numantine warriors, Rhetogenes, led a small party over the walls, down the river, and through the barricade. They went to their fellow tribesmen for aid, but the Aravaci were too fearful of Roman power to join the conflict. Rhetogenes then went to the Lutians, where he got a more positive response from the younger warriors of the tribe. The older citizens counseled against aid, however, and they warned Scipio of the planned relief. Scipio left a holding force at Numantia and marched to Lutia and surrounded it. He demanded and received the 400 young men who responded to Rhetogenes, then cut off their hands so they could offer no assistance. He then resumed his siege at Numantia.

Seeing his hope of aid gone, the Numantine leader Avarus sent envoys to negotiate with Scipio. Thy offered to surrender in return for their city’s liberty. Scipio refused, demanding unconditional surrender. When the envoys returned to the city with Scipio’s response, the population did not believe their report. Thinking the envoys had cut a separate deal, the people killed them.

Unable to sally and unwilling to surrender, the Numantines starved. Anything that could be used for food was consumed, even the bodies of their own dead. There are reports of some people killing weaker citizens for consumption, rather than waiting for them to die. Disease soon compounded the starvation process, and the few remaining citizens began considering conceding to Scipio’s demands. Rather than face the shame of such an outcome, many of the survivors chose death over dishonor, killing their families and then themselves. The last survivors surrendered to Scipio, but only after setting their city ablaze.

Results

Sources differ on the length of the siege, some saying eight months and others sixteen. Late summer 133 b.c. is the generally accepted time of the surrender. Upon receiving the surrender of the remnants of the population, Scipio ordered the ruins of the city leveled. For a cost of virtually no casualties of his own, Scipio removed the Numantine threat from Roman occupation of Iberia. By the time of the Third Celtiberian War the Aravaci had been a serious local power; after Numantia’s fall what resistance remained was scattered.

In 77 b.c. another Iberian rising challenged Roman power in the Numantia area, and the general who suppressed it was Pompey, one of the Triumvirate that was instrumental in Julius Caesar’s rise to power. Caesar later was appointed consul in Iberia and in order to enhance his own military and political reputation, he raised a local force and conquered Galicia, the last holdout of Celtic resistance in the peninsula. It was that conquest, in 59 b.c., which finally secured Roman rule over all Iberia.