Maneuvers before and after the Battle of Nineveh

The wars between Persia and Rome came to a climax between 603 and 628, with significant consequences for each empire and for subsequent world history. Sparked by mutual interference in each other’s dynastic disputes, Chosroes II of Persia opened the wars against the emperor Phocas, who murdered his own predecessor, Maurice, who had helped Chosroes gain the Sassanid throne. But with initial success against an East Rome both politically divided-Heraclius overthrew Phocas in 610, assuming command of Roman forces-and threatened by a major Avar invasion in the Balkans, Chosroes’s ambitions grew. By 615, he had conquered Syria and Armenia, the latter a major Roman recruiting area; then, between 616 and 619, he conquered Egypt, cutting off Constantinople’s main grain source. With forces established across the Bosporus from Constantinople in 616, Chosroes allied with the Avars; the new allies approached the mighty city in 619. East Rome was on the verge of extinction, and the empire of Darius on the verge of being reestablished.

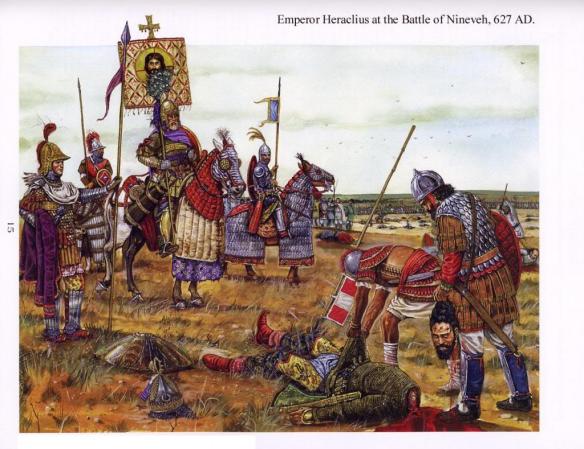

Heraclius nearly fled to Africa, but a religious revival led by the patriarch Sergius convinced him to stay, and the church then provided resources for rebuilding the Roman position. Heraclius bought off the Avars and used his naval superiority to renew the war in Syria, drawing the Persians away from his capital. Then, in a daring and brilliant series of campaigns between 623 and 627-during which Constantinople was besieged in 626-he bypassed the reconquest of the provinces completely, striking directly into the heart of Persia. At the decisive battle of Nineveh in 627, he routed the Persian army and pursued the survivors to the gates of the Persian capital of Ctesiphon. The Persians killed Chosroes, installed his son Kavadh II as king, and accepted terms that returned all of Chosroes’s conquests to Roman rule.

It was an amazing recovery, but one that was to be undone rapidly from an unforeseen quarter, in part by the consequences of the sort of warfare each side waged, for both the religious and political impact of the wars spread beyond the confines of the two empires. Some historians have come to call Heraclius’s campaigns against the Persians the first “crusade” because of the importance that Christianity assumed for the morale and fighting spirit of the troops under his command. They marched with crosses on their banners, and the notion of being surrounded by enemies but backed by God contributed to a growing sense in Constantinople that the eastern Christians were a Chosen People. But, of course, similar sentiments opposed the Romans on the other side: These wars could be considered both the first and the last Zoroastrian crusades. At the same time, both sides, given the desperation of the struggle, looked for any allies they could find. The Avars played this role for a time for the Persians, but for the most part, both sides looked to Arab client kingdoms to the south for manpower and diversionary attacks. The result was a flow into Arabia of wealth in the form of bribes to enemies and subsidies to allies, linked to intense ideological pressure in the form of monotheistic religions. This inflow prepared the ground for surprising state formation and religious creativity by one Arab leader in particular, the Prophet Muhammad. What the resulting Arab religious state would meet were two exhausted empires and provinces in Syria and Egypt only recently reintegrated into the structures of Roman rule.

The nature of the Arab conquests is grounded in pre- Islamic Arabia, which can best be compared to the steppes of Central Asia. A fringe of settled, agricultural land and trade-oriented cities along the western and southern edges of the peninsula bordered a vast desert, too poor to support horse herding as in Central Asia and so dominated by camel-herding Bedouins (nomads). The poverty of the land had two consequences. First, unlike the steppe nomads, the Arabs could not generate the resources for building hierarchical chiefdoms and states themselves-in fact, they could barely do so with outside infusions of wealth. Such infusions were, in turn, less likely because the Arabs were neither as numerous nor, usually, as threatening as the steppe nomads. And the Arab border with civilization was at the opposite end of the peninsula from the economic center of gravity of the Arab world, further complicating potential state building. Second, the lack of competition for poor land meant that, again unlike the steppes and its constant churning of peoples and ethnic identities, Arab tribal culture and identities were extremely stable and deeply rooted, and so potentially more resistant to assimilation by the cultures of surrounding civilizations. Deep tribal divisions also contributed to the difficulties faced by would-be state builders, however.

But the half-century of intense East Roman- Sassanid Persian rivalry up to 630 created some new potential, politically and culturally. Economic resources came in, religious rivalries heated up, and Muhammad turned out to be the right leader at the right time to harness that potential. Whatever the details of his new faith and his role in it, he clearly managed to create a state centered at Medina. In competition with other Arab political groups, Muhammad’s Medina benefi ted from the ideological lure of a religion that drew on Arab notions of ethnic identity through their claimed descent from Abraham via Ishmael, that therefore incorporated the Christian and (even more important) Jewish traditions already in the area, that also managed to absorb the Arab pagan tradition, and that justified Arab unity and external conquest in the name of a universal god. Muhammad died in 632 having built Arab unity and (probably-the sources are unclear) initiated attacks into Roman Syria. His successors built rapidly on his foundation.

Persia, along with large but varying parts of Mesopotamia and regions to the east and north bordering India and the Central Asian steppes, respectively, had come gradually under Parthian control in the first century BCE, highlighted by the Parthian victory over Roman forces at Carrhae in 53 BCE. The Parthians, originally steppe nomads, continued to dominate the area into the third century, though their political control was more in the way of a loose confederation than a unitary empire, and they generally acknowledged the superiority of Rome in upper Mesopotamia. Around 200, a series of civil wars seriously weakened Parthian power. Ardashir, governor of the central Persian region of Persis, consolidated his control of the heartland of Persian power in the decade after 200 and then challenged his Parthian overlords. By 226, he had defeated the Parthian ruler and proclaimed his dynasty, the Sassanids, as the successors of the Achaemenids of Cyrus the Great and Darius.

Ardashir thus reestablished a consciously Persian identity for the imperial power of southwest Asia, an identity intimately tied up with Zoroastrianism. Under the Achaemenids, this had been a predominantly elite religion that ruled tolerantly over a multitude of local religious traditions. But the Sassanids promoted Zoroastrianism in ways that, while retaining its vital ties to the Persian aristocracy and its legitimization of royal power and the Persian state, made it a more popular religion. Rulers encouraged conformity of practice and perhaps belief, developing an equation of Zoroastrianism not just with “Persianness” but with loyalty to the monarchy. This coincided with a rebuilding of Persian military power around a traditional core, the heavy cavalry forces of the Persian aristocracy, backed by infantry and archers drawn from the broader population and inspired by wider adherence to Zoroastrianism.

Sassanid Persia and East Rome went to war chronically between 230 and 600, usually struggling for control of the rich provinces of Mesopotamia, with the Persians dominating in the south and the Romans more successful in the north, nearer their bases in Asia Minor. Roman organization and military engineering, especially the strength of their fortifications, tended to be balanced fairly evenly against Persian advantages in mobility and cavalry skill and in theaters of conflict that lay closer to Persian centers of power than to Roman ones. The wars tended toward indecisiveness and often ended in a truce by mutual agreement to avoid fiscal crisis. Both empires also faced enemies on other fronts-East Rome in the Balkans and Persia in the borderlands to the Asian steppes to the north-that forced their attention elsewhere.

These wars in the last half of the sixth century became more intense, partly militarily but partly ideologically, as the clash of Christian and Zoroastrian universalisms fueled a rivalry that was already fierce simply on political and economic grounds. The Sassanids, in particular, learned lessons in organization and statecraft from their Roman neighbors. As a result, the political structure of the Sassanid Empire became, like East Rome’s, progressively more centralized over the course of the sixth century while, again like East Rome, its religious culture became more militant externally and more intolerant internally (though a host of smaller religious traditions continued to exist in the spaces between the great powers, especially in culturally heterogeneous and fragmented southern Mesopotamia).