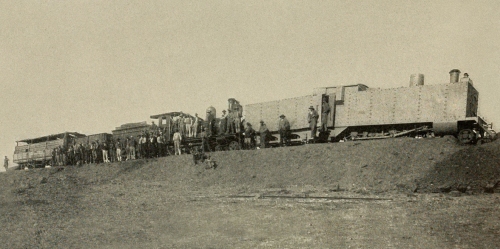

An armoured CGR 3rd Class 4-4-0 1889 locomotive derailed on 12 October 1899 during the first engagement of the Second Boer War at Kraaipan.

Armoured trains were another innovation that made their first significant appearance in the American Civil War. The idea of armoured trains was almost as old as the railways and the earliest were probably the improvised trains used by the Austrians to help quell the revolts. The first American armoured trains were built to patrol the railroads north of Baltimore against Confederate saboteurs, which was, according to the standard work on the subject, ‘the earliest example of armored trains performing their classic role of antipartisan warfare’.

In the South, General Lee, ever innovative, conceived of using them in an offensive way with a rail-mounted gun. At the battle of Savage Station in June 1862, a 32-pounder mounted on a flat car and protected by strong oak planking on the sides and roof, was pushed along by a train. It was, however, of limited use since it was confined to the railroad line, ensuring it had a restricted field of attack. The Federals also showed interest in the idea and an ‘ironclad railway battery car’ was manufactured at the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Pittsburgh in August 1862. It was a bizarre beast, a 30-foot-long flat car with a 6in cannon mounted on a revolving platform, and protected on the sides. Union military director and superintendent of the railroads Herman Haupt was not impressed, and shunted it into an old siding, but the idea gradually took hold and several of these cars were eventually produced and saw active service in the later stages of the war, being hitched to the front of a locomotive to give maximum vision and reach, and pushed along. Armoured trains were, though, a sideshow, as they would, with several notable exceptions, remain.

When the British Army began to invade the Boer republics, the Department of Military Railways spawned a separate organization, the Imperial Military Railways, both to repair and maintain captured lines in the two republics, and to operate them. The Afrikaners employed by these railways were unwilling to stay in their jobs under the British and therefore had to be replaced by soldiers and railwaymen from the Cape Colony and, later, also by local black workers.

As the British troops headed northwards, elaborate patrols were devised using armoured trains to protect the line, which was absolutely vital for the British advance. It was the first time that armoured trains were extensively and successfully operated in any conflict. The British had deployed them in Egypt, Sudan and India in the 1880s, using conventional rolling stock that was reinforced with steel plating and equipped with a few machine guns and sandbags for protection, and often pushing a light wagon at the front to detonate mines or limit the damage from obstacles left on the line. They were little more than armoured patrol vehicles, but during the Boer War far more sophisticated versions were developed.

Several had been built in anticipation of the war and ultimately twenty saw action on the South African railways. Their reputation was initially rather tarnished by the capture on 15 November 1899 of an early model carrying 120 men including, famously, Winston Churchill, who yet again had made sure that he was in the right place at the right time to see action. This time, he was a mere reporter, sending despatches to the Morning Post although at times he behaved as if he were still an officer in the British Army. Churchill recounts an early sortie with the train, which he describes as a strange machine, ridiculing it as ‘a locomotive disguised in the habiliments of chivalry. Mr Morley [John Morley, the leading opponent of the war] attired as Sir Lancelot would seem scarcely more incongruous.’ His first foray with the train passes off without serious incident but his second leads to his capture and a series of brushes with death.

Churchill’s train had consisted of a couple of sets of four vans, three of which were armoured, including one with a 7-pounder gun so old-fashioned that it was still loaded through the muzzle (‘an antiquated toy’, as Churchill described it), an ordinary wagon with a breakdown gang and a locomotive which, for protection, was in the middle of the train between the two sets of wagons. The patrol’s mission was to try to obtain information about the siege at Ladysmith and the state of the railway. At 5.30 a.m., the train crept out of Estcourt, thirty miles south of Ladysmith, and had reached Chieveley, about halfway to their destination, when Boer horsemen were spotted. Captain Haldane, the commander of the train, decided to beat a retreat but the train had fallen into an ambush. Round a curve, they saw a large troop of 600 Boers above them and bullets and shells started raining down on the wagons. The engine driver opened the regulator to accelerate out of trouble, which was precisely what the Boers had sought, as the train then ploughed at speed into a boulder they had laid on the tracks round a bend. Even though the train was notionally in the command of Haldane, it was Churchill who assumed control of the situation, or at least he did according to his account written for the Morning Post. He reports how he told the driver, who was a civilian and therefore anxious just to escape, that ‘if he continued to stay at his post, he would be mentioned for distinguished gallantry in action’, not an honour that was Churchill’s to bestow. Nevertheless, with such encouragement, the fellow ‘pulled himself together, wiped the blood off his face [and] climbed back into the cab of his engine’. Leaving Haldane to sort out the defence, Churchill organized the removal of the debris and the stone from the tracks, and ordered a group of men to push the broken wagon off the track. Despite being still under fire, they succeeded and the engine, minus the front group of trucks, which had become detached, gradually pulled away. All these efforts to escape proved, however, to be in vain because, as Churchill describes it, ‘a private soldier who was wounded, in direct disobedience of the positive orders that no surrender was to be made, took it upon himself to wave a pocket handkerchief.’ As a result, the men around him began to surrender and Churchill tried to run away. While Churchill criticizes the hapless fellow, the humble soldier’s action most likely changed history by ensuring the great man’s survival. Churchill had already run down the track with two Boers shooting at him, fortunately missing him on either side (‘two bullets passed, both within a foot, one on either side… again two soft kisses sucked in the air, but nothing struck me’), and had fortuitously, too, forgotten his Mauser pistol in the cab of the locomotive, and was therefore unable to shoot his pursuers. Without the private’s white handkerchief, it was probably only a matter of minutes before Churchill, who was behaving as a combatant rather than a newspaper reporter, would have been shot. After his capture, however, anxious to be released, he stressed his civilian role but to no avail and he was imprisoned in Pretoria, from where he escaped, regaining British territory by jumping goods trains like an American hobo.

Churchill’s armoured train was an early version, more lightly armed than its successors. Later types would be far more heavily protected and were successfully used on several occasions against the Boers. The armoured train became a far more sophisticated weapon, consisting of a locomotive in the middle, pushing armoured vans and wagons with various pieces of equipment for repairing lines. At the front, there was an open wagon fitted with a cow catcher – like US locomotives – both to sweep obstructions off the rails but also to explode mines, thereby saving the rest of the train, particularly the locomotive, from further damage. Behind the locomotive there was a heavily armoured wagon with usually a 12-pounder quick-firing gun or a couple of smaller ones. Each end of the train would be protected by armoured trucks containing soldiers armed with rifles and a machine gun. It proved a useful weapon. In one skirmish, the legendary Boer leader Christiaan de Wet, who had been instrumental in developing successful guerrilla tactics, often focussed on sabotaging the railway and disrupting communications by wrecking the telegraph wires, was for once caught napping when four armoured trains managed to cut him off from his wagons and he lost all his ammunition and explosives.

While armoured trains were occasionally used in offensives against entrenched Boer positions, for the most part they were deployed to patrol lines in an effort to prevent sabotage. They were also used rather like the cavalry to make reconnaissance trips and escort conventional trains. Nevertheless, as Churchill’s mishap showed, they were vulnerable to ambush and could not be deployed without their own protection force, usually in the form of cavalry reconnaissance teams who would check the line and the surrounding area but at times bicycles were used, too. These were remarkable contraptions developed in a Cape Town workshop by Donald Menzies, who experimented with various types. The basic version, which did see regular active service, involved two men sitting side by side, with the great advantage that they could ride and shoot at the same time, since, obviously, no steering was required as the wheels were flanged like those of all railway rolling stock. It could travel at up to 30 mph but was not stable at such high speeds and generally cruised at about 10 mph. Menzies also produced a huge eight-man version with four pairs of men pedalling side by side, but it was beset with difficulties as it was too heavy – 1,500lb with eight men aboard – and consequently was difficult to brake, made too much noise and caused violent shaking, and there is no evidence that it was actually used in combat situations.

The official report published after the war recommended that in the operation of armoured trains ‘it was important that the officer commanding the train should be a man of judgment and strong nerve… he had to be ever alert that the enemy did not cut the line behind him… and had to keep his head even among the roar which followed the passage of his leading truck over a charge of dynamite, and then to deal with the attack which almost certainly ensued’. Inevitably, having such strong-minded officers in charge of the trains led to clashes with the railway authorities as the armoured trains transcended the boundary between the military and railway. Girouard later complained that the officers commanding the trains frequently rode roughshod over the railway’s needs: ‘Armoured trains were constantly rushing out, against orders of the Traffic department, sometimes without a “line clear” message, and this caused serious delays to traffic.’ One can almost feel Girouard’s frustration as he continues: ‘In fact, instead of assisting traffic by preventing the enemy from interrupting it, they caused more interruptions than the enemy themselves.’ As Pratt put it, ‘civil railway officials were heard to say that attacks by the enemy are not nearly so disturbing to traffic as the arrival of a friendly General with his force’. Regulations were subsequently issued to ensure that the armoured trains, like all other traffic, deferred to the army officers whose job was to liaise with the railway authorities to ensure efficient use of the lines.

The armoured trains proved popular with the British and were a formidable weapon, causing panic among the enemy, as stressed by an officer who had served in them: ‘There is no doubt that the enemy disliked them intensely and that the presence of an armoured train had a great morale effect.’ The post-war report rather optimistically outlined seven uses for armoured trains, including obvious aspects such as reconnoitring, patrolling and protecting the rail lines, along with more adventurous ideas like ‘serving as flank protection to infantry’ and ‘attempting to intercept the enemy’. While for the most part this analysis overemphasized their usefulness, since armoured trains would play little role on the Western Front in the First World War, they would assume much greater importance on the more fluid Eastern Front and, in particular, would be crucial to the Bolsheviks’ victory in the subsequent Russian civil war. In the Boer War, they were used to best effect to counter guerrilla attacks, a role they would play numerous times again.

The armoured train was a natural development of the basic idea of mounting guns on trains, which, as we have seen, was first used in battle in the American Civil War. Such trains were a railway weapon, likely to be deployed in an offensive action, in contrast to armoured trains whose main purpose was to patrol an unstable area. The concept of using the railways to deploy large artillery guns had made considerable progress since the days of General Lee. In particular, the problem of aiming the guns had been solved to some extent by incorporating a turntable on the car, which enabled the gun to be rotated easily, and methods of dispersing the force of the recoil, using a specially constructed chamber, had also been developed, enabling guns to be fired broadside without toppling over or damaging the track. The French had used a couple of rail-mounted guns to defend Paris during the siege in 1871 and a unit of the Sussex Army Volunteers had experimented with putting a 40-pounder on a rail wagon. As a result of these developments, the British Army tried to make use of a pair of mobile guns built in the workshops of the Cape Government Railway during the Boer War. In the event they were little used in anger, principally because of the difficulties of bringing such unwieldy and slow vehicles within range of a battle site on a single railway track already heavily used by conventional traffic.