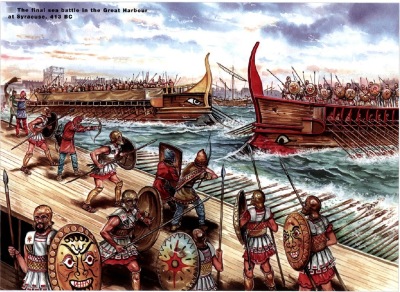

The final sea battle in the Great Harbour at Syracuse, 413 BC. The largest single expedition that Athens mounted in the Peloponnesian War was to Sicily in 415 BC, consisting of 134 triremes. Reinforcements of 73 triremes followed the next year. In the first sea battle the Syracusans manned 76 triremes. Yet in spite of their advantage in numbers and skill, poor leadership meant that the Athenian armada was trapped in the Great Harbour, where their skill could not be exercised. The outcome in 413 BC was to be a total disaster.

Based on Thucydides 7.70, this reconstruction shows the first impetus of the Athenian attack, which carried them through the Syracusan vessels guarding the boom across the harbour mouth. The Athenians began loosening the chained merchantmen, but then other Syracusan warships joined in from all directions and the fighting became general throughout the harbour. Thucydides emphasizes that it was a harder sea-fight than any of the previous ones, but despite the best efforts of the Athenian helmsmen, because there were so many ships crammed in such a confined space, there were few opportunities to maneuver-and-ram, backing water (anakrousis) and breaking through the enemy line (diekplous) being impossible. Instead, accidental collisions were numerous, leading to fierce fights across decks and much confusion. In other words, this was an engagement in which Athenian skill was nullified.

Date 415–413 BCE

Location Syracuse in Sicily

Opponents (* winner) *Syracuse and Sparta Athens and its allies

Commander Gylippus Alcibiades, Lamachus, Nicias, Demosthenes

Approx. # Troops Sparta: 4,400; Syracuse: Unknown but probably equal to Athens and allies 42,000

Importance Leads to revolts against Athens from within its empire

The siege of the city-state of Syracuse in Sicily by Athens and its allies during 415-413 BCE initiated the final phase of the Second Peloponnesian War (431- 404 BCE). Alcibiades, a nephew of Pericles, convinced Athenians that if they could secure Sicily they would have the resources to defeat their enemies. The grain of Sicily was immensely important to the people of the Peloponnese, and cutting it off could turn the tide of war. The argument was correct, but securing Sicily was the problem.

The Athenians put together a formidable expeditionary force. A contemporary historian, Thucydides, described the expeditionary force that set out in June 415 as “by far the most costly and splendid Hellenic force that had ever been sent out by a single city up to that time” (Finley, The Greek Historians, 314). The naval force consisted of 134 triremes (100 of them from Athens and the remainder from Chios and other Athenian allies), 30 supply ships, and more than 100 other vessels. In addition to sailors, rowers, and marines, the force included some 5,100 hoplites and 1,300 archers, javelin men, and slingers as well as 300 horses. In all, the expedition numbered perhaps 27,000 officers and men. Three generals—Alcibiades, Lamachus, and Nicias—commanded.

The original plan was for a quick demonstration in force against Syracuse and then a return of the expeditionary force to Greece. Alcibiades considered this a disgrace. He urged that the expeditionary force stir up political opposition to Syracuse in Sicily. In a council of war, Lamachus pressed for an immediate descent on Syracuse while the city was unprepared and its citizens afraid, but Alcibiades prevailed.

The expedition’s leaders then made a series of approaches to leaders of the other Sicilian cities; all ended in failure, with no city of importance friendly to Athens. Syracuse used this time to strengthen its defenses. Alcibiades meanwhile was recalled to stand trial in Athens for impiety.

Nicias and Lamachus then launched an attack on Syracuse and won a battle there, but the arrival of winter prevented further progress, and they suspended offensive operations. What had been intended as a lightning campaign now became a prolonged siege that sapped Athenian energies. Alicibades, fearing for his life, managed to escape Athens and find refuge in Sparta. He not only betrayed the Athenian plan of attack against Syracuse but also spoke to the Spartan assembly and strongly supported a Syracusan plea for aid. The Spartans then sent out a force of their own commanded by Gylippus, one of their best generals.