PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Syria (Seleucids) vs. Rome (with Rhodes and Pergamum)

PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Asia Minor

DECLARATION: Rome on Syria, 192 B.C.E.

MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Syria wanted Rome’s compliance in the conquests of its ally Aetolia.

OUTCOME: Rome attacked a Syrian fleet, triggering a war that proved disastrous for the Syrians, who lost their seaports and became landlocked.

APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS:

Syrian forces, 75,000; Roman-Pergamenian forces, 40,000

CASUALTIES: Unknown

TREATIES: None

Following the defeat of Macedonia at the Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197, during the Second MACEDONIAN WAR, the Aetolians of central Greece jockeyed for position to take Macedonia’s place as the dominant state in Greece. After attacking the allies of Rome among the Greek states, they appealed to Syrian king Antiochus III (the Great; 242–187 B.C.E.) to intervene with Rome on their behalf.

Taking this as an invitation from the Aetolian League to invade Greece, Antiochus sailed with an army of 10,000 across the Aegean in 192 and was met by a Roman army at Thermopylae. Under the leadership of M. Acilius Glabrio (d. 152 B.C.E.), the Roman forces defeated Antiochus, who fled with the remainder of his forces back to Ephesus. However, the naval fleets of Rhodes and Pergamum collaborated with the Romans against Antiochus’s navy, winning three victories at sea, first at a location between Ionia and Chios (191 B.C.E.), then at Eurymedon and Myonessus, both in 190 B.C.E.

Polyxenidas

Polyxenidas a Rhodian general and admiral, who was exiled from his native country, and entered the service of Antiochus III the Great, king of Seleucid Empire. We first find him mentioned in 209 BC, when he commanded a body of Cretans mercenaries during the expedition of Antiochus into Hyrcania . But in 192 BC, when the Syrian king had determined upon war with Rome, and crossed over into Greece to commence it, Polyxenidas obtained the chief command of his fleet. After co-operating with Menippus in the reduction of Chalcis, he was sent back to Asia to assemble additional forces during the winter.

We do not hear anything of his operations in the ensuing campaign, 191 BC, but when Antiochus, after his defeat at the Battle of Thermopylae (191 BC) , withdrew to Asia, Polyxenidas was again appointed to command the king’s main fleet on the Ionian coast. Having learnt that the praetor Gaius Livius Salinator was arrived at Delos with the Roman fleet, he strongly urged upon the king the expediency of giving him battle without delay, before he could unite his fleet with those of Eumenes II of Pergamon and the Rhodians. Though his advice was followed, it was too late to prevent the junction of Eumenes with Livius, but Polyxenidas gave battle to their combined fleets off Corycus. The superiority of numbers, however, decided the victory in favour of the allies ; thirteen ships of the Syrian fleet were taken and ten sunk, while Polyxenidas himself, with the remainder, took refuge in the port of Ephesus.

Here he spent the winter in active preparations for a renewal of the contest; and early in the next spring (b. c. 190), having learnt that Pausistratus, with the Rhodian fleet, had already put to sea, he conceived the idea of surprising him before he could unite his forces with those of Livius. For this purpose he pretended to enter into negotiations with him for the betrayal into his hands of the Syrian fleet, and having by this means deluded him into a fancied security, suddenly attacked him, and destroyed almost his whole fleet. After this success he sailed to Samos to give battle to the fleet of the Roman admiral and Eumenes, but a storm prevented the engagement, and Polyxenidas withdrew to Ephesus. Soon after, Livius, having been reinforced by a fresh squadron of twenty Rhodian ships under Eudamus (Rhodian), proceeded in his turn to offer battle to Polyxenidas, but this the latter now declined. Lucius Aemilius Regillus, who soon after succeeded Livius in the command of the Roman fleet, also attempted without effect to draw Polyxenidas forth from the port of Ephesus : but at a later period in the season Eumenes, with his fleet, having been detached to the Hellespont while a considerable part of the Rhodian forces were detained in Lycia, the Syrian admiral seized the opportunity and sallied out to attack the Roman fleet.

The action took place at Battle of Myonessus near Teos, but terminated in the total defeat of Polyxenidas, who lost 42 of his ships, and made a hasty retreat with the remainder to Ephesus. Here he remained until he received the tidings of the fatal battle of Magnesia, on which he sailed to Patara in Lycia, and from thence proceeded by land to join Antiochus in Syria. After this his name is not again mentioned.

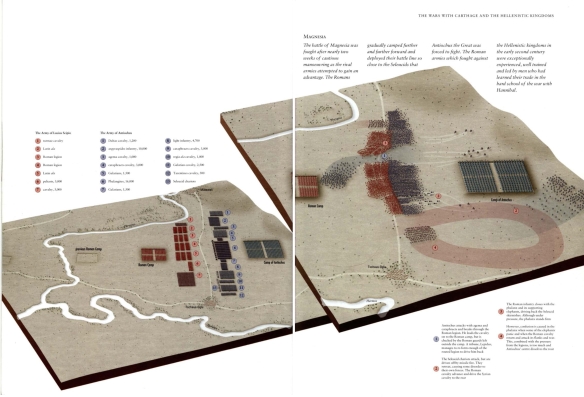

The Romans capitalized on these triumphs by invading Asia Minor with an army under the command of two great generals, Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (237–183 B.C.E.) and his brother Lucius Cornelius Scipio (fl. second century). They met the Syrians at the Battle of Magnesia near Smyrna in December 190. After initial gains, Antiochus III made a serious tactical blunder by pursuing a flank of the Roman cavalry too far, laying himself open to encirclement by another Roman flank. This infantry force destroyed most of the Syrian army. As a result, Syria gave up all of its coastal territories, surrendered all but 10 of its warships, gave up its war elephants, and agreed to pay a heavy indemnity. Landlocked, Syria’s power was greatly diminished.

Further reading: John D. Grainger, Roman War of Antiochos the Great (Boston: Brill Academic, 2002); Susan Sherwin-White and Amelie Kuhrt, From Samarkhand to Sardis: A New Approach to the Seleucid Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).