Emperor Franz Joseph started to regather and rearm an army to be commanded by Anton Vogl, the Austrian lieutenant-field-marshal who had actively participated in the suppression of the national liberation movement in Galacia in 1848. But even at this stage Vogl was occupied trying to stop another revolutionary uprising in Galacia. The Czar was also preparing to send 30,000 Russian soldiers back over the Eastern Carpathian Mountains from Poland. Austria held Galacia and moved into Hungary, independent of Vogl’s forces. On August 13, after several bitter defeats in a hopeless situation, Görgey signed a surrender at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians.

In the early months of 1848 France was in a ferment over the country’s franchise. Louis-Philippe ‘ King of the French by the Grace of God and the Will of the People’, had attempted to establish a constitutional monarchy on the British pattern. But the solid basis of a sound tradition was lacking and malcontents at each end of the social scale were quick to criticize shortcomings while ignoring the good points: the 1830 barricades were, after all, still a vivid memory.

On February 24, 1848, the industrial population of the Paris faubourgs stormed into the city, and the luckless Louis-Philippe was forced to flee to Great Britain.

The spirit of revolt quickly spread to other countries, the vast and heterogeneous Austrian Empire being a predestined victim. Riots broke out in Vienna, and Metternich escaped on March 13 to commiserate with Louis Philippe in England.

The Austro-Hungarian Army at this time still wore the white short-tailed jacket, but the headdress was now a cylindrical shake .Regimental distinctions continued to be shown by the color of the collar, cuffs and turnbacks combined with the white metal or brass of the buttons.

One of the most interesting revolts. however, occurred on March I, 1848 at Neuchatel, That territory-which, incidentally, had produced de Meuron’s Regimen t for the Dutch and British services, as well as Berthier’s yellow-coated battalion for Napoleon – had been ceded to Prussia after the Napoleonic wars, and many of the ‘Canaries’ joined the newly formed Prussian Gardeschütze-Bataillon for service in Berlin. Fortunately for them, because they were then spared the agonizing duty of having to fire on their own countrymen when the latter marched down from the Jura Mountains to attack the castle at Neuchatel. The Prussians were soon overcome, the inevitable republic proclaimed, and Neuchatel became a Swiss canton.

The Prussian troops had now taken the famous spiked helmet into wear- but in a much taller version than the familiar 1914 pattern. The tunic was beginning to replace the long-skirted coat, and long trousers were being worn in preference to breeches and gaiters.

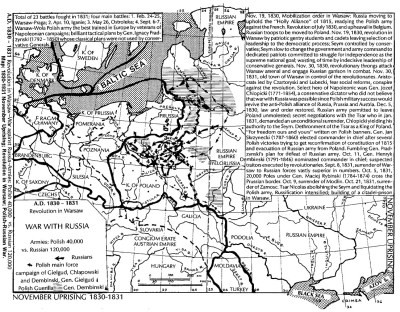

The most dramatic surge of resistance to the conservative order came in Poland, where in November 1830 the patience of the patriotic Polish nobility within the Russian partition snapped when the Tsar mobilised the Polish army in response to the revolutions in Western Europe. The insurrection lasted ten months and was crushed – after some bloody and intense fighting – by a 120,000- strong Russian army under General Ivan Paskevich (who would help repress another revolution in 1849). In the retribution that followed, a staggering eighty-thousand Poles were dragged off in chains to Siberia.

Poland sat uneasily under Russian rule. The revolutions of 1830 provided inspiration for Polish revolutionaries, and a ticking clock. Poland would soon be occupied by massive numbers of Russian troops preparing for foreign intervention, meaning revolution had to come quickly or not at all. In November 1830, Polish cadets and junior officers launched a coup in Warsaw. They occupied public buildings, Warsaw crowds seized weapons from a government arsenal, and Russian authority evaporated. Nicholas’s brother Constantine, governor of Poland, escaped capture but begged Nicholas to show restraint. Constantine’s hopes for moderation were dashed. The Polish insurgents grew increasingly radical, formally deposing Nicholas as king of Poland at the beginning of 1831. Nicholas in turn resolved to crush this by force.

As in the two preceding wars, Russia found it difficult to employ its potential strength effectively. Nicholas’s troops invaded Poland in February 1831, and the early clashes were inconclusive enough to give Poles some hope of success. The spring thaw of 1831 turned roads to mud and delayed Russian progress, along with supply problems, a cholera epidemic, and harassment by Polish partisans. Finally, at the end of May, the Poles suffered a major defeat at Ostroleka, and the cohesion of Polish resistance broke down. A Russian army reached Warsaw in September 1831, and resistance collapsed. Thousands of Poles went into exile in western Europe, boosting an already-burgeoning wave of Russophobia. Nicholas was restrained in his reimposition of order in Poland, though the separate Polish army was abolished and its troops integrated into Russian forces.