Northern and western Europe

The archaeological evidence indicates that from at least as early as the second millennium BC seagoing ships were making their way between the coasts of northern and western Europe, carrying people and goods over long distances. We have already noticed the importance of skin or hide boats in colder waters and it is clear from several Classical Roman writers that this type of vessel was considered highly suitable for the mariners of France, Ireland and the British mainland. A framework of relatively slender timbers with hides stretched over it was also very light in weight, which was another useful feature for mariners who would often need to carry their craft over considerable distances and also be in need of extra buoyancy. Both sails and oars were used for propulsion, but very large oared galleys of the Mediterranean type were employed by the Romans only when their naval forces operated in northern waters.

Early medieval seafarers in north-western Europe and Scandinavia used the virtually double-ended vessels with upswept prow and stern characteristic of many later medieval craft. These features enabled the ships to be beached and launched easily and were useful when running before the wind, which seems to have been a favoured sailing technique. The building method was usually shell-first and consisted of light, overlapping planks, laid clinker-fashion, fastened to the keel by lashing, strengthened by strakes and attached to each other by iron clenches. By the ninth century ad Nordic shipwrights had developed a vessel type with a fairly broad keel that relied mainly on a single square sail for propulsion, with the oars being an auxiliary power source for use in calm weather or inland waterways. The typical Viking raiders’ ship was a buoyant, fast sailing vessel that needed very little depth of water and few or no docking facilities.

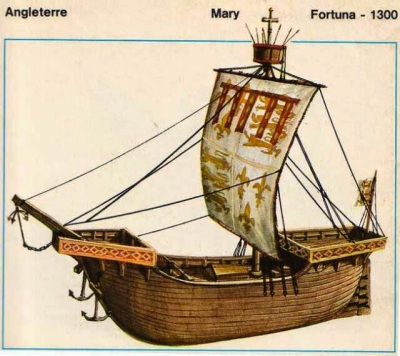

Ship designs were adapted to suit the needs of the communities that used them. The Norwegian and Danish vessels that crossed the North Sea and the Atlantic were generally smaller than the Swedish ones that operated in the Baltic, sacrificing carrying capacity for seaworthiness in the harshest of conditions. By the thirteenth century the Scandinavians and their Germanic neighbours were using bulkier, less elongated ships for trade and even military activity. There were two predominant types, the hulk, or hulc, a word which originally seems to have meant something hollowed out like a peapod and was characteristically banana-shaped, with a curving hull, high prow and stern, but little or no sternpost or stempost. Side rudders were commonly used for steering. A good depiction of this type can be seen on the fourteenth-century seal of Winchelsea. The hulk may have originated in the Low Countries, but it spread to England and across northern Europe and was the most common cargo vessel of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The other was the cog, probably of Frisian origin, and distinguished by its angled prow and stern, flat bottom and high sides. The cog was the preferred vessel of the Hanseatic traders in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Both had a main square sail on a mast fitted amidships. Gradually larger sails and more masts were added. Stern-castles and fore-castles were used on both merchant and naval ships. One reason for the development of the hulk and the cog may be that harbour duties and maritime taxes encouraged merchants to use fewer, larger ships. Another reason may be the adoption of the centrally mounted stern rudder, gradually introduced to northern Europe in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, which could be more easily incorporated in these types of ships. It has also been argued that high-sided sailing ships were more difficult for pirates to attack. By the sixteenth century, however, three-masted ocean-going vessels based on a sturdier, more flexible skeleton-first form of ship construction began to replace these earlier types.

The ships that launched European seafarers across the oceans of the world in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries represent a combination of design and construction elements from the maritime traditions of the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean and northern Europe. The caravels that were the favoured ships of the Portuguese in the fifteenth century had blunt, transom-built sterns with large rudders. They were carvel-built, that is with the planks joined edge-to- edge, rather than overlapping in the northern style. They could carry both square and lateen rigged sails, as Vasco da Gama’s fleet did in his epic voyage to India, using the former style in the Atlantic, but converting to the latter style in the Indian Ocean.

Over the next few centuries the main developments in European shipping were in terms of size and speed. Sailing ships were made larger and sleeker, and were rigged with more masts and sails to use the available winds as effectively as possible. Displacements of a few hundred tons were typical of the ships of the late sixteenth century, but in later centuries ships displacing a thousand tons or more were built. Bulk cargoes, carried over long distances in large, fast ships also required protection. The Spanish, needing to transport the wealth of the New World in large amounts and securely, developed the most celebrated ship of the sixteenth century, the galleon, a long, single- or double-decked, ocean-going ship with sharply raised foredeck and quarter-deck and a hull pierced with ports for heavy guns. It was the increasing number of guns on the European warships of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that were to make them particularly effective against the ships and coastal fortifications of the Orient. The Chinese, for example, had long used artillery in warfare, but they did not employ large guns on their ships.