| Figure 1. “Goke” an Ottoman war ship. Miniature taken from Katip Celebi’s manuscript Tuhfetü’l-kibar. Topkapi Palace Library, R. 1192. |

The Ottoman state that was founded in northwest Anatolia expanded its territories towards the west and the north and reached the coast within a short time period. While the conquest of Istanbul was a step for the Ottoman state to extend its hegemony worldwide, Ottoman navigation gained a new centre. The new centre of the state, Istanbul, started to develop as the centre of Ottoman navigation. Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror, having noticed the mild and deep waters of the Golden Horn appropriate for a maritime arsenal, appointed the Commander of the Navy, Hamza Pasha, for The construction of a maritime arsenal.

The term tersane has entered the Turkish language after many usages of the Arabic word dar al-Sina’a by various Mediterranean countries throughout centuries. Arsenal from dar assina`ah meaning ‘house of making/industry’ like a factory was borrowed into Venetian Italian, somehow loosing its initial d, as arzanà, and was applied to the large naval dockyard in Venice. The dockyard is known to this day as the Arzenale. English acquired the word either from Italian or from French arsenale, using it only for dockyards. By the end of the 16th century it was coming into more general use as a ‘military storehouse.’ The Ottomans were using the word “port” instead of maritime arsenal, but from the beginning of the sixteenth century onwards, they started to use the term tershane or tersane which was similar to the Italian usage of the word.

The pictures of the late fifteenth century, depicting galleys anchored or repaired in the Golden Horn, point to the fact that the arsenal was functioning. The Ottoman fleet which was built in the Gallipoli Maritime Arsenal (Figure 1) that continued to be the Ottoman naval base in this period and the newly-established Istanbul maritime arsenal dominated the Black Sea and seized Otranto under the command of Gedik Ahmed Pasha (1480).

|

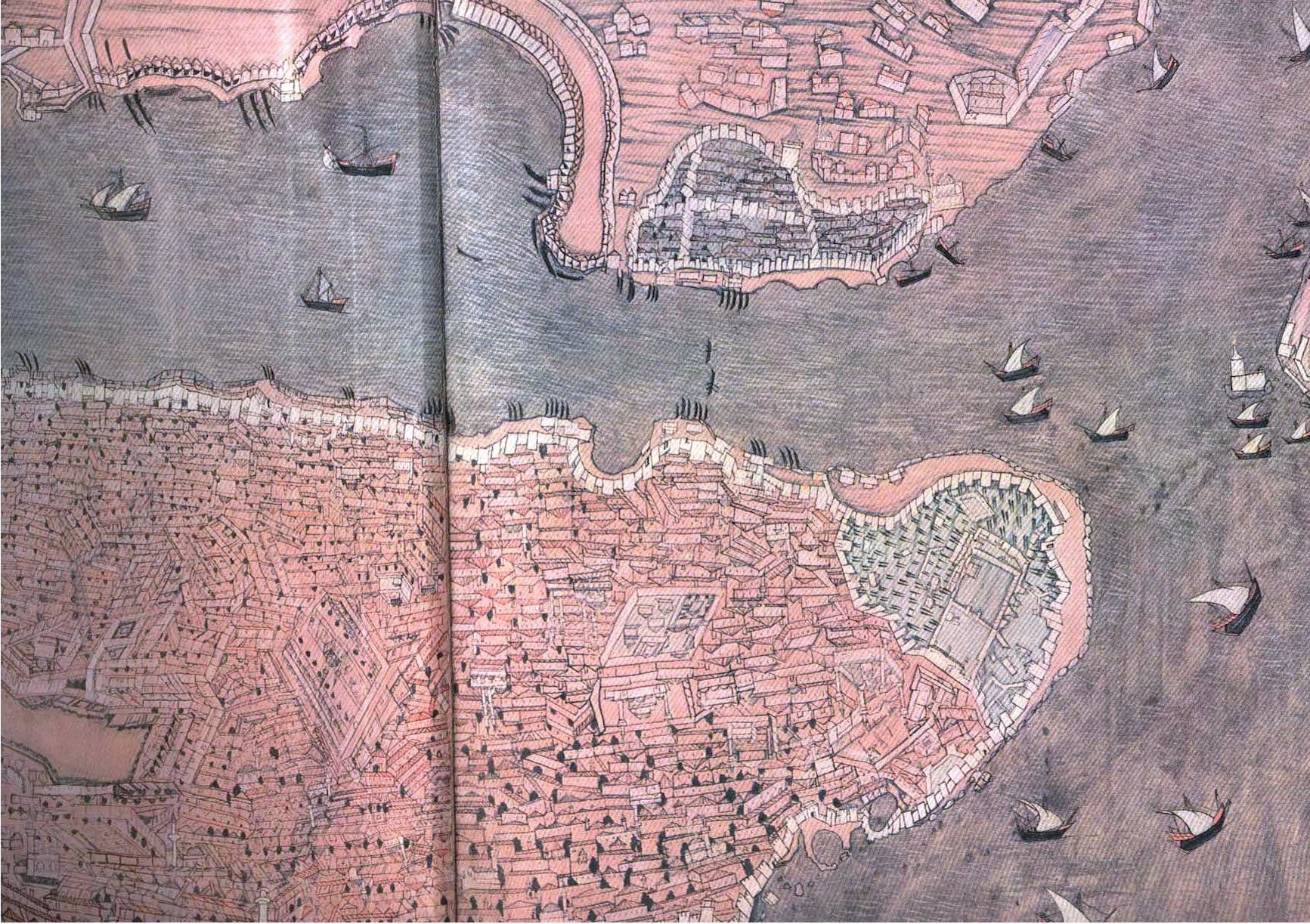

| Figure 2. The Imperial Arsenal (Halic) map drawn by Velican in the XVIth century. Hunername minyaturleri ve sanatcilari. Istanbul: Yapi ve Kredi Bankasi, 1969. |

The basic modification in the Istanbul Maritime Arsenal was made during the reign of Sultan Selim I (1512-1520), who wanted to be strong in the seas as well as in the lands, and sought to expand the Istanbul Maritime Arsenal to have a greater fleet. Upon his return from the Caldiran campaign, he expressed his views to the Grand Vizier Pirî Mehmed Pasha as follows: “If these scorpions (Christians) are occupying the seas with their ships, if the flags of Doge of Venice, the Pope and the kings of France and Spain are waved in the coasts of Thrace, this is because of our tolerance. I want a very strong navy large in number as well.” Upon this, Pirî Pasha replies as follows: “My Excellency, you just stated what I would like to present. Scold me, especially, when we come to your presence with the other viziers. Order immediately for the construction of a maritime arsenal and five-hundred warships. The Franks will be frightened when they hear this news. You will see that before the completion of the yards and the laying out to the sea of forty galleys, they will come demanding for the renewal of the treaties and payment of taxes. By this way, most of our expenditures will be met by their payments.

After these meetings, they paid attention to the maritime arsenal and naval affairs. The maritime arsenal construction that had started in the area extending from Galata to Kagithane River under the supervision of Admiral Cafer was completed in 1515. In this construction, 50,000 coins were spent for each section and 150 ships were ordered to be built. By this way, the Galata (Golden Horn, Istanbul) maritime arsenal that would serve as the constructive and administrative centre of the navy was established.

As a matter of fact, Sultan Selim I had turned his attention towards the seas when he came back from the Egyptian campaign. He had previously seized important ports in the Eastern Mediterranean, such as Syria and Egypt and he regarded it as vital to conquer Rhodes which was on the route that connected these states to the Ottoman Empire. Because it was necessary to stop the Saint-Jean L. Hospitality knights of Rhodes, who would possibly threaten the commercial ships passing through, and to provide for the security of those who would visit the Holy Land. To this end, it was crucial to have Rhodes and other islands under the Ottoman control. Thus realising this fact, Sultan Selim I spent his last years with the preparation of a huge fleet. However, the conquest of Rhodes was accomplished by his son, Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent.

The Main Maritime Arsenal continued its development during the times of Sultan Suleyman and his son, Selim II. During the times of Hayreddin Barbarossa Pasha (Figure 2) and other famous seamen that he trained, the Arsenal served as the central base of the fleet which materialised the Ottoman hegemony. In this period, the maritime arsenal extended from Azapkapisi to Haskoy. Among its outhouses were sections that were approximately two hundred in number where shipbuilding and reparation took place, various ammunition depots, production studios, administrative buildings, a mosque, a dungeon, a bathhouse and fountains. With these facilities provided, the Istanbul Maritime Arsenal became the most famous one worldwide in the sixteenth century. A similar one existed only in Venice.

| |

| Figure 3. The statue of Barbaros Khayreddin Pasha in Istanbul. |

In the development of the Main Maritime Arsenal, known also as the Galata Maritime Arsenal, some Grand Admirals such as Guzelce Kasim Pasha, Hayreddin Barbarossa Pasha (Figure 3) and Sokullu Mehmed Pasha played an important role. From 1515 on, the activities of the maritime arsenal were transferred from Gallipoli to Istanbul and the Galata maritime arsenal had become the central base.

The Gallipoli Maritime Arsenal

The first biggest and orderly Ottoman maritime arsenal is built in Gallipoli. During the construction that had started in 1390, the damaged outer wall of the Gallipoli castle was pulled down and the inner castle on a hill was strengthened. The artificial port composed of two pools in each side for the ships to take shelter. Also, for security reasons two towers were built in the entrance of the port that could be closed with a chain. Together with this port, there were shipbuilding yards, equipment preservation depots, fountains to provide water for the ships, bakeries for the ship’s crackers, and gunpowder depots which made the Gallipoli maritime arsenal a complete state maritime arsenal.

Despite the establishment of a new maritime arsenal in Galata with the conquest of Istanbul, the Gallipoli maritime arsenal had kept its importance until the end of the reign of Sultan Selim I. Moreover, Gallipoli had become the settlement area and a central sanjak of the province of Cezayir-i Bahr-i Sefid in 1534.

After the assignment of Gallipoli to maritime arsenal and navigation affairs, during the first years of the Ottoman state, the indigenous Greeks appointed to work were paid salaries and some others were paid wages called harac ispenc and avariz-i divaniyye in the ship-building and reparation and the maintenance of the pool.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, with the development of the Galata Maritime arsenal, the Gallipoli Maritime arsenal became the second rank in importance and was used only when there was a need for ship-building. The Gallipoli Maritime arsenal which had 30 pools in 1526 was repaired from time to time in later stages.

The Ottomans increased their naval power towards the end of the fifteenth century. They adapted technical terms in navigation and navigation experiences from their Western neighbours and especially from the Venetians. They increased the number and type of their ships and established their hegemony in the Mediterranean in the first half of the sixteenth century.

| |

| Figure 4. An Ottoman kalyon, a war ship and naval army personnel. From http://www.turkkorsanlari.com/ |

THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE OTTOMAN NAVY

The administrative staffs of the Ottoman navy were divided into two: Navy High Officials and Main Maritime Arsenal High Officials. Among the Navy High Officials were the navy commanders and the admirals who worked with them and the other servants on the ships. The Main Maritime Arsenal Officials included the workers in the Maritime Arsenal.

The military and civilian head above these ranks working in the Navy and the Maritime Arsenal was the Grand Admiral of the Ottoman Fleet (Kapudan Pasha). Previously, the Grand admirals used to serve as the sanjak beys of Gallipoli. In later stages, they were appointed as the governor-general of the province of Cezayir-i Bahr-i Sefid that was established with the joining of Barbaros Hayreddin Pasha to the Ottoman fleet, and by the end of the sixteenth century they obtained the rank of vizier.

The Ottoman Empire, which was building the greatest fleets in the world with huge personnel, was facing the problem of dispatching and administration of these fleets as they were put out to sea. The preparation of thousands of oarsmen in each expedition and the provision of the food for them necessitated a separate form of organisation.

For this reason, in the sixteenth century, with its presence in the Mediterranean, the Black Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Ottoman Empire looked like a Seaborne Empire. Even though it had been influenced by Western states and especially by the Venetians, regarding the shipbuilding technology and navigation techniques, in time, it established a Nautical Organisation and had it maintained through modifications throughout centuries.

by: FSTC Limited, Sun 28 January, 2007