Potentially a major, advance in air warfare, the Gotha bomber was Germany’s major weapon in her attempt to subdue England’s civilian population in World War I. From it arose the misguided belief that terror bombing could win wars.

‘How is it, after three years and a half of war, that such raids can be undertaken over London with impunity, and that these Gothas should escape unscathed ?’ This question, asked in the British House of Commons and reported in the ‘Daily Express’ of 30 January 1918, typified the concern felt about the effects of the terrible innovation of ‘aerial bombardment by heavier-than-air’ machines of a civilian population, wrought by the German Gotha GV, its most formidable exponent to that date. There was also more than a touch of politicking in the question for, in 1918, improved British defenses against the Gotha, coupled with its unreliability, particularly in bad weather, were steadily reducing its effectiveness.

But this was little consolation to the Londoners who, attracted by the uneven throb of aircraft engines, had stared into the mid-morning sky on 13 June 1917. People pointed up towards the 14 gleaming white planes that cruised steadily southwards at a height of 15,000ft. There was even some patriotic cheering to welcome what was assumed to be a British patrol. Then suddenly the harsh bark of anti-aircraft guns reverberated in the warm air—the aircraft were German. Astonished faces showed a realization that the hated enemy could fly above the nation’s capital in broad daylight.

High above the city in his twin-engined Gotha, Captain Ernst Brandenburg identified the famous landmarks coming into view below him. Behind Brandenburg’s lead ship, his squadron deployed to commence the attack. Then the bombs rained down on the capital. Many of the people in the area of the attack seemed too stupefied even to take cover.

High explosive bombs fell across the eastern dock area at 1135. Five minutes later, 72 bombs landed around Liverpool Street Station, a main rail terminus and the Germans’ main target. Their mission complete, and hardly daring to hope that they might get away safely, the Gothas headed east for the North Sea and their bases near Ghent, in Belgium. In London the capital mourned 162 dead. The concept of the long-range strategic bomber attacking major urban centers was born and with it the Gotha legend.

The original Gotha was a clumsy twin-engined biplane, with the fuselage suspended from the upper wing. It was evaluated operationally by the Germans in 1915. Between 12 and 20 GIs (G for Grossflugzeug, or ‘large aircraft’) were built before the end of 1915, but work was already proceeding on a superior design, the GII.

This new Gotha was a far more elegant biplane than the GI. The fuselage was mounted in orthodox fashion on the lower wing. There were three crew positions—the observer, usually the captain, sat in the nose with a swivelling Parabellum machine-gun, a connecting corridor led to the pilot’s cockpit, and the third member of the crew was the rear gunner, whose position was level with the trailing edges of the wings. The 220hp Mercedes DIV engines drove pusher propellers and were installed in bulky nacelles which incorporated fuel and oil tanks.

The GII proved to be gratifyingly fast for its day, with a maximum speed of 82mph, and ten were ordered. Operational units on the Balkan front began using them towards the end of 1916, initially with 14 22lb bombs in an internal bomb bay but later with additional bombs fitted on external racks.

Two major shortcomings were known even before the GII went into action: the straight-8 Mercedes engines suffered from recurrent crankshaft failures and there was no defensive armament to protect the blind spot beneath the tail. Both of these problems were rectified in the GIII. Six-cylinder 260hp Mercedes DIVa power plants were fitted, and a machine-gun was mounted on the floor of the rear cockpit that fired downwards through an aperture in the bottom of the strengthened fuselage.

Both the Gil and the GIII were flown by Kagohl 1 (Kampfgeschwader 1 of the OHL, or Oberste Heeresleitung) in the Balkans. Operating from Hudova, they proved remarkably successful, especially in the bombing of Salonika and the destruction, in September 1916, of a vital railway bridge over the Donau at Cernavoda. The Gothas did not have it all their own way, however, and a Royal Flying Corps scout pilot who encountered a formation of six Gothas over Macedonia in March 1917 shot down two of them before his ammunition ran out. The GIII also served on the western front with Kagohl 2 at Freiburg, and the French ace Guynemer claimed one, shared with another French pilot, as his 31st kill on 8 February 1917.

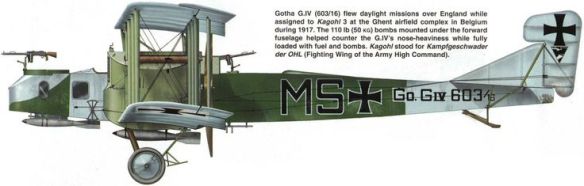

The next Gotha type, the GIV, differed only in detail from the Gill, the most significant alteration being the incorporation of the famous Gotha ‘tunnel’. This was a long opening cut out of the bottom of the fuselage from the rear gunner’s position back to the tail: it enabled the upper gun to be directed downwards through a small triangular aperture in the top decking to fire at any hostile fighter attempting to approach the bomber’s blind spot. When fully or half loaded, the GIV proved to be a stable aircraft to fly, at the same time retaining a high degree of manoeuvrability; once empty, however, it was difficult to handle, with a pronounced nose-heavy trim—crash landings, as a result, became commonplace.

The GIV was the aircraft that was to undertake Germany’s Operation Turk’s Cross, the aerial bombardment of Britain by heavier-than-air machines in support of the airship raids that were already in progress. A special squadron, designated Kagohl 3 and soon to be known as the England Geschwader, was formed with this express object.

The Gothas were scheduled for delivery by 1 February 1917, and in the meantime crews went to Heligoland-and Sylt for training in the techniques of navigating over the open ocean. In 1916 the bleak waters of the North Sea were a formidable barrier to aircraft and, as insurance, the GIV’s plywood-covered fuselage was designed to enable a ditched plane to remain afloat for several hours.

Production delays held up delivery of the GIV to the England Geschwader until March 1917. The squadron was now commanded by the 34-year-old Captain Brandenburg with six constituent flights of six Gothas located at Mariakerke, St. Denis Westrem and Gontrode.

After two months with the G IV’s the England Geschwader was ready to launch Turk’s Cross. Brandenburg’s first attempt to raid England ended at Nieuwmunster when last-minute storm warnings led to a cancellation of the mission. On Friday, 25 May 1917, at 1700, however, twenty-one Gothas flying at 12,000ft crossed the Essex coast. Their target was London, but as they reached the Thames near Gravesend, only 20 miles from their objective, bad weather forced them to turn south in search of alternative targets. The Gothas scattered bombs haphazardly across Kent until they reached Hythe, where they headed eastwards along the coast. Late in the afternoon they arrived over Folkestone.

The little coastal town had no warning of the impending catastrophe. One moment the sunlit streets were packed with cheerful shoppers, the next they were shattered by German bombs. Amid the smoke, dust, splintered glass and ruined masonry, the dead and dying lay in grotesque, blood-soaked heaps.

One Gotha 95 dead

The Gothas made the best of their escape, harassed out to sea by anti-aircraft fire from Dover and a handful of fighters. A British naval squadron at Dunkirk was sent up to cut off the raiders’ retreat and succeeded in bringing down one Gotha, while another was lost near Bruges. These were the only German casualties. In England, 95 people had died and 195 were injured.

Brandenburg had now lost the element of surprise for his first raid on London so another attack on British coastal targets was mounted on the evening of 5 June. Twenty-two Gothas bombed Shoeburyness and Sheerness. Anti-aircraft fire brought down one bomber, but this time the RNAS squadron at Dunkirk was out of luck, for Brandenburg had arranged for German fighters from Flanders bases to cover his withdrawal.

On 13 June 1917 the Gothas first reached London. Of the 20 German bombers that had taken off, only 14 reached the British capital.

Of the 20 German bombers that had taken off, only 14 reached the British capital. The June 13 bombing raid destroyed property and killed civilians and this brought home the idea that England was an island no more, but it would appear that at least one of the most emotional reasons was the death of the 16 kindergarten children at the Upper North Street Schools.

After pounding London, north and south, the Gotha flight reformed and on their way out, dropped the remaining bombs they had for the run home. Tragically, one bomb hit a school building, broke in two, one piece crashed through three floors, killing two students but did not explode until it landed in the basement where 64 infants were being supervised. The 16 were blown apart, many were terribly mutilated. Only two of the 16 were older than five years of age. Not only had the war brought the bombers to England but it was killing the children in the sanctuary of their creches.

It wasn’t until a week later that the victims were buried in a common grave in the East End after a very impressive funeral service and procession in which each child had its own horse drawn hearse. Granted this was only part of the reason for bringing back the fighter squadrons (who proved ineffectual for various reasons) but it was no doubt the most powerful emotional response from a society unused to the idea of their homes and families being in such danger. Some of the funeral wreaths (over 500) read “To our children, murdered by German aircraft.”

On his return, Brandenburg was flown to Kreuznach to receive the Pour le Merite from the Kaiser. As he took off for the return flight his plane’s engine spluttered and he crashed. Brandenburg was dragged from the wreck alive, but the disaster cost him a leg.

At the end of June the new commanding officer of Kagohl 3 arrived, 30-year-old Rudolf Kleine. On 4 July he led his first raid, directed, because of poor weather, against the coastal town of Harwich. Twenty-five Gothas took off, and although seven turned back with engine trouble before they reached the English coast, both Harwich and nearby Felixstowe were successfully attacked.

Valiant but suicidal gesture

Only three days later, on Saturday 7 July, the Gothas appeared over London again, 22 strong. But before the raiders had reached the English coast British fighters were in the air to intercept. Among them, in a Sopwith 14-Strutter, was 19-year-old Lieutenant John E. R. Young with Air Mechanic C. C. Taylor as rear gunner. The Sopwith climbed steadily out to sea until the massed bomber formation was-spotted approaching on a collision course. Lt. Young aimed his aircraft straight at the oncoming Gothas. It was a valiant but suicidal gesture. The frail biplane was bracketed by concentrated fire from the score of German aircraft. Bullets riddled the Sopwith’s wings and fuselage, killing both the crew instantly. Lieutenant F. A. D. Grace of 50 Squadron from Dover had better fortune and shot a homeward-bound Gotha into the sea. Four other bombers crashed at their bases trying to land in gusty wind. Bombs fell on widely scattered targets, mostly in the north-eastern parts of the city, killing 57 people and injuring 193.

Gothas raided Harwich on 22 July and for the next raid, on 12 August, Chatham was the objective, with Southend and Margate as secondary targets. British fighters, 109 in all, were up to meet them. Unteroffizier Kurt Delang, flying only his second mission over England, was forced to take violent evasive action in his heavily laden Gotha as a scout flashed by in a firing pass. He frantically rolled the big bomber to left and right as the British fighter came in again from behind. Machine-gun bullets crashed into one of the Gotha’s ailerons and threw the plane on its starboard wing tip. The over-confident Englishman closed for an easy kill —and missed I As the scout swooped below the Gotha and climbed for another attack, Delang’s gunners found their mark at last, and the British fighter dived away with smoke pouring from it.

Southend and Margate, together with Shoeburyness, were bombed, and all the Gothas escaped though four suffered landing accidents at their Belgian bases, and two aborted from the mission due to engine trouble.

Anxious to redress this setback, Kleine ordered another raid for 18 August. Despite clear skies, his meteorological officer forecast severe winds over England and advised against the mission. Kleine ignored the warning and took off. The result of his impetuosity was the disaster of ‘Hollandflug’. Strong south-westerly winds swept the Gothas over neutral Holland, where AA guns opened fire. After three hours of buffeting they finally reached England, some 40 miles north of their intended landfall. With fuel running dangerously low, Kleine was forced to turn back, but the Gothas were swept across the North Sea by a gale that again blew them towards Holland. At least two planes ditched, others were forced down in Holland and Belgium, and many of those which did finally reach Ghent crashed on landing.

What was left of the England Geschwader, a mere 15 planes, made their last daylight attack on Britain only four days later. A third of the force aborted en route, including Kleine himself, and the remainder succeeded only in inflicting minor damage on Ramsgate, Margate and Dover. The raiders were beaten off by unprecedentedly fierce anti-aircraft file, which claimed one Gotha, and well coordinated fighter interceptions, which accounted for two more.

It was now clear that England was too well defended for further daylight raids, and the GIVs were proving increasingly unreliable due to the use of inferior petrol and the declining quality of the materials employed in their construction. In addition, the machines most recently delivered to England Geschwader were licence-built aircraft manufactured by the Siemens-Schuckert and LVG concerns which embodied strengthened—and therefore heavier—airframes. Their performance was markedly inferior to that of the original Gotha-built GIVs, and bombing heights had declined from over 16,000ft on the first England raid to 13,000ft or less. The LVG machines also proved to be tail heavy and had to have the sweepback of the wings increased to counteract this shortcoming.

The answer to the problem of heavy losses in daylight raids and reduced performance was to attack at night. On 3-4 September four volunteer crews, led by Kleine, took off in a hazy night with a full moon. The targets of the trial raid were Chatham, Sheerness and Margate. Anti-aircraft fire was sporadic and British fighter planes were not equipped for night flying. A bomb dropped on Chatham hit a naval barracks and 132 ratings were killed. Of the attack on the naval barracks, the ‘Evening News’ of Wednesday 5 September stated that ‘Reports from the Chatham area all appear to indicate that the damage in that district was the work of only one raider. Eight or ten bombs were dropped, and one fell on a portion of a Royal Naval Barracks, which was fitted with hammocks for sleeping, and 107 blue jackets were killed and 86 wounded. It is feared that two or three of the injured will not recover … The raiding machine is believed to have been of the Gotha type. All the German planes returned safely from the raid.

The next night nine Gothas set out to attack London. Only five reached the city which was not blacked-out and glittered like a beacon to guide Kleine’s crews. The ‘Evening News’ on 5 September led with ‘Invasion by moonlight’ and described the effects of the attack in various parts of London. ‘Some of the bombs’, the newspaper reported, ‘as they fell caused a sharp whistling sound ; and when they exploded there was little or no report . . . Other missiles, however, gave very loud reports—louder than those which were remembered in connection with the Zeppelin raids.’ The civilian population, having their first taste of night bombardment by heavier-than-air machines, apparently kept calm : ‘There was no panic among the inhabitants, but large numbers of women and children living in houses near the Tube rushed for shelter below ground, and were taken down in the lifts to the underground platforms.’ The sky was streaked with searchlights and anti-aircraft guns opened fire—but their effect was, according to the ‘Evening News’, ‘not apparent’. The first Gotha night raid on London cost 19 dead and 71 injured. It also caused £46,000 worth of damage.

By this time Kagohl 3 were taking delivery of the Gotha GV. The GV had a lighter but stronger airframe than the GIV, with the fuel tanks removed from the engine nacelles (where they frequently burst in the event of a crash) to the fuselage. As a result of this re-location of the fuel, there was no longer a gangway connecting the rear gunner’s position with the cockpit. Despite a gross weight of nearly 9,0001b, the maximum speed had risen to 87mph with a ceiling of 21,000ft.

From 24 September to the night of 1-2 October, a week of bright moonlight, Britain was subjected to a concentrated series of raids in which the Gothas were joined for the first time by some of the huge German R-planes. London suffered six attacks in this period, including one Zeppelin raid, and the resulting chaos was out of all proportion to the damage and casualties sustained by the capital. The Germans did not escape unscathed, however, and for the England Geschwader, it was a costly campaign. Five Gothas were brought down by the defenses, and eight more crashed on their return to Belgium.

Kagohl 3 was now also required to operate against targets on the western front, but another major raid on London was mounted on the night of 31 October-1 November, when 22 Gothas set out carrying incendiary bombs in addition to their usual high explosives. Due to strong winds and low cloud, bombs were scattered haphazardly on Dover, Chatham, Gravesend, Herne Bay, Ramsgate, Margate and Canterbury as well as the eastern environs of London.

One Londoner described the bombing of his house to the ‘Star’ of 1 November: ‘The man said that they heard the raider humming overhead and were looking at the shell bursts through the window’, the ‘Star’ reported. ‘ “The humming became louder . . . and then I heard a whistling noise. There was a bright green flash and a fearful concussion. The house shook to its foundations, and I thought it was going to crack. The wardrobe in the corner of the room was thrown over, and we were nearly choked with fumes and dust. A mass of plaster from the ceiling crashed down and a large piece just missed the heads of my children. We escaped from the building by the staircase, which was undamaged”: His experience was clearly more frightening than that of another Londoner, reported in the ‘Star’ the same day—he slept through ‘ “the whole business. He refused to get up while the raid was on”.’ British casualties in this raid were fairly light as most of the incendiary bombs failed to ignite. Five Gothas, however, crashed in fog when trying to land at their bases.

Bad weather halted operations against Britain until the moon returned at the end of November. On the night of 5-6 December, a total of 19 Gothas plus two R-planes were dispatched to raid London and various Kent coast towns. The losses, however, were becoming prohibitive. Two Gothas were brought down by anti-aircraft fire, one was apparently lost in the sea, two more barely managed to limp back to Belgium, and another crashed on landing.

On 12 December Kleine was killed during a daylight raid on British troop encampments near Ypres. His 17 Gothas were bounced by three Royal Flying Corps Nieuports at 10,000ft over Armentieres. Captain Wendell W. Rogers, a 20-year-old Canadian pilot of No 1 Squadron RFC, closed to within 30ft of the tail of Kleine’s Gotha and poured a sustained burst into the huge bomber, which began to glide steeply down towards the trenches below. At 4,000ft it burst into flames: two of the crew jumped without parachutes, the third died as the plane crashed and exploded in No Man’s Land near Warneton.

The Gothas appeared again in the night skies above Britain on the evening of 28 January 1918. Because of low-lying mist in Belgium, only 13 bombers were able to take off, and six of these turned back over the North Sea; only three of the remainder reached London, the other four attacking Sheerness, Margate and Ramsgate. German losses comprised one Gotha brought down in flames by two Camels from 44 Squadron Hainault Farm and four lost in crashes at their fog-bound bases.

An alarming casualty rate

Kagohl 3 was still carrying out raids on French ports and over the front, but casualties were mounting at an alarming rate. At the beginning of February, Ernst Brandenburg returned to take command again, but after one look at what remained of the England Geschwader he had the unit taken off operations to re-organize and re-equip. By the spring of 1918, Kagohl 3 was once more flying combat missions over France and the western front, but they did not attack England again until 19 May.

The raid on 19-20 May was the largest to be mounted against Britain during the whole war, 38 Gothas and three R-planes flying the mission. From 2230 until long after midnight the bombers streamed across to London, and destruction was extensive with over a thousand buildings damaged or destroyed. But the Gothas paid a fearful price. Only 28 of those that took off actually attacked England; fighters claimed three victims, anti-aircraft fire accounted for three more, and one crashed on its return flight.

As had happened with the GIV, the performance of the GV deteriorated as loads increased and serviceability declined, and the 19 May raid had been carried out from only about 5,500ft, whereas earlier night missions with GV’s had been at over 8,000ft. Bombing at such low levels was bound to be expensive.

By June 1918 new types of Gotha were beginning to arrive at Kagohl 3. The GVa and GVb both had shorter noses than the normal GV, box-tails with twin rudders instead of a single fin and rudder, and auxiliary landing wheels under the nose or at the front of each engine nacelle. The GVb could carry a useful load of 3,520lb, 8031b more than earlier models, but its performance was otherwise no better and in some respects inferior. Since the GIV was now obsolete, these aircraft were being supplied to the Austrians for use on the Italian front, or to training squadrons in Germany.

At the end of May the England Geschwader were switched exclusively to targets in France in support of the German spring offensive, including Paris and Etaples, on the French coast. Later they were diverted to tactical targets near the front as the Allies counter-attacked, and the squadron inevitably suffered catastrophic losses. By November it was all over, however, and grandiose schemes to renew the raids on England in 1919 came to nothing as Germany sued for peace.

The casualties suffered by Kagohl 3 at the end of hostilities totalled 137 dead, 88 missing and over 200 wounded. On raids against England alone, 60 Gothas were lost—almost twice the basic strength of the unit. But the Gotha threat kept two British front line fighter squadrons at home at any one time and thereby indirectly benefited the German Air Force in France and Flanders.

It has been suggested that the Gotha was a copy of the British Handley Page 0/100, an example of which fell into German hands at the beginning of 1917, but this is incorrect. The 0/100 had 275hp Rolls Royce engines giving it an endurance of eight hours with a bomb load of nearly 1,8001b compared with the Gotha’s of six hours endurance and about 1,100lb bomb load.

The consequences of the German raids on England during World War I were far reaching, and the symptoms of panic which they invoked in London led to a mistaken belief that bombing attacks could break the morale of civilian populations. The potential of bombers in the ‘1930s was greatly exaggerated and it was feared in 1938 that the Luftwaffe could pulverize London in a matter of weeks. The bogey of the bomber was certainly an influential factor in persuading the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, to sign the notorious Munich agreement of September 1938.

In 1940, however, the Luftwaffe’s bombers proved too small to accomplish the destruction of London and the Germans came to regret their neglect of the four-engined heavy bomber.

On the British side, the defensive network evolved in 1917-18 formed a basis for the more sophisticated system used in the Battle of Britain, while belief in the power of the bomber led to the appearance of the four-engined Lancasters, Halifaxes and Stirlings that were used to systematically burn-out the major cities of Germany.