The Airco DH.9 (from de Havilland 9) also known after 1920 as the de Havilland DH.9 was a British bomber used in the First World War. A single-engined biplane, it was a development of Airco’s earlier, highly successful DH.4 and was ordered in very large numbers for Britain’s Royal Flying Corps and Royal Air Force.

An unreliable engine which did not deliver the expected power meant, however, that the DH.9 had poorer performance than the aircraft that it was meant to replace. This resulted in heavy losses to squadrons equipped with the DH.9, particularly over the Western Front. It was subsequently developed into the DH.9A with a more powerful and reliable engine.

Design and development

The DH.9 was designed by de Havilland for the Aircraft Manufacturing Company in 1916 as a successor to the DH.4. It used the wings and tail unit of the DH.4 but had a new fuselage. This enabled the pilot to sit closer to the gunner/observer and away from the engine and fuel tank. The other major change from the DH.4 was the choice of the promising new BHP/Galloway Adriatic engine, which was predicted to produce 300 hp and so give the new aircraft an adequate performance to match enemy fighters.

By this time, as a result of attacks by German bombers on London, the decision was made to almost double the size of the Royal Flying Corps, with most of the new squadrons planned to be equipped with bombers.[1] Based on the performance estimates for the DH.9 (which were expected to surpass those of the DH.4), and the similarity to the DH.4, which meant that it would be easy to convert production over to the new aircraft, massive orders (4,630 aircraft) were placed.

The prototype (a converted DH.4) first flew at Hendon in July 1917.[2] Unfortunately, the BHP engine proved unable to reliably deliver its expected power, with the engine being de-rated to 230 hp in order to improve reliability. This had a drastic effect on the aircraft’s performance, especially at high altitude, with it being inferior to that of the DH.4 it was supposed to replace. This meant that the DH.9 would have to fight its way through enemy fighters, which could easily catch the DH.9 where the DH.4 could avoid many of these attacks.

While attempts were made to provide the DH.9 with an adequate engine, with aircraft being fitted with the Siddeley Puma, a lightened and supposedly more powerful version of the BHP, with the Fiat A12 engine and with a 430 hp Napier Lion engine, these were generally unsuccessful (although the Lion engined aircraft did set a World Altitude Record of 30,500 ft (13,900 m) on 2 January 1919[3]) and it required redesign into the DH.9A to transform the aircraft.

Operational history

The first deliveries were made in November 1917 to 108 Squadron RFC, with several more squadrons being formed or converted to the DH.9 over the next few months, and with nine squadrons operational over the Western Front by June 1918.

The DH.9’s performance in action over the Western front was a disaster, with heavy losses incurred, both due to its low performance, and engine failures (despite the prior de-rating of its engine). For example, between May and November 1918, two squadrons on the Western Front (Nos. 99 and 104) lost 54 shot down, and another 94 written off in accidents.[4] The DH.9 was however more successful against the Turkish forces in the Middle East, where they faced less opposition, and it was also used extensively for coastal patrols, to try and deter the operations of U-boats.

Following the end of the First World War, DH.9s operated by 47 Squadron and 221 Squadron were sent to southern Russia in 1919 in support of the White Russian Army of General Denikin during the Russian Civil War.[5] The last combat use by the RAF was in support of the final campaign against Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (known by the British as the “Mad Mullah”) in Somalia during January—February 1920.[5] Surprisingly, production was allowed to continue after the end of the war into 1919, with the DH.9 finally going out of service with the RAF in 1920.[6]

Following the end of the First World War, large number of surplus DH.9s became available at low prices and the type was widely exported (including aircraft donated to Commonwealth nations as part of the Imperial Gift programme.[3]

The South African Air Force received 48 DH.9s, and used them extensively, using them against the Rand Revolt in 1922. Several South African aircraft were re-engined with Bristol Jupiter radial engines as the M’pala, serving until 1937.[7]

Civilian use

Because of the large number of surplus DH.9s available after the war many were used by air transport companies. They provided a useful load carrying capability and were cheap. Early air services between London, Paris and Amsterdam were operated by DH.9s owned by Aircraft Transport and Travel. A number of different conversions for civil use were carried out, both by Airco and its successor the de Havilland Aircraft Company and by other companies, such as the Aircraft Disposal Company.[8] Some radial powered DH.9Js continued in use until 1936.[9]

Variants

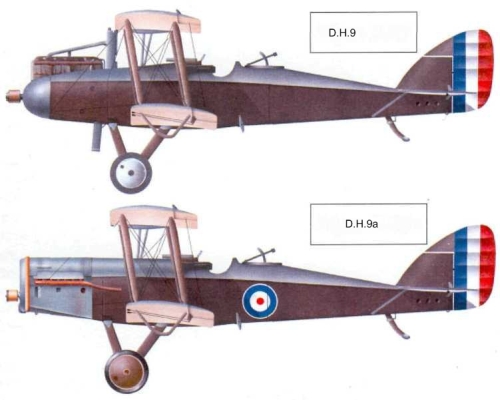

- DH.9 – Revised version of the DH.4 with the pilot and observer/gunner placed closer together (3,024 production aircraft built with others built in Belgium and Spain).

- DH.9A – (also referred to as the Nine-Ack) was designed for Airco by Westland Aircraft to take advantage of the American Liberty L-12 400 hp (298 kW) engine. Apart from the new engine and slightly larger wings it was identical to the DH.9. Initially it was hoped to quickly replace the DH.9 with the new version – however a shortage of Liberty engines available to the RAF curtailed the new type’s service in the First World War – and it is best known as a standard type in the postwar RAF – serving as a general purpose aircraft for several years. 2,300 DH.9As were built by ten different British companies.

- DH.9B – Conversions for civilian use as three-seaters (one pilot and two passengers)

- DH.9C – Conversions for civilian use as four-seaters (one pilot and three passengers)

- DH.9J – Modernised and re-engined conversions using the 385 hp (287 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Jaguar III radial piston engine. Used by the De Havilland School of Flying.

- DH.9J M’pala I – Re-engined conversions carried out by the South African Air Force. Powered by a 450 hp (336 kW) Bristol Jupiter VI radial piston engine.

- M’pala II – Re-engined conversions carried out by the South African Air Force, powered by a 480 hp (358 kW) Bristol Jupiter VIII radial piston engine.

- Mantis – Re-engined conversions carried out by the South African Air Force, powered by a 200 hp (149 kW) Wolseley Viper piston engine.

- Handley Page HP.17 – A DH.9 experimentally fitted with slotted wings [10]

- USD-9 – DH.9s manufactured in the United States by the US Army’s Engineering Division (1,415 built)

Specifications (D.H.9 (Puma Engine))

Data from The British Bomber since 1914[6]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 30 ft 5 in (9.27 m)

- Wingspan: 42 ft 4⅝ in (19.92 m)

- Height: 11 ft 3½ in (3.44 m)

- Wing area: 434 ft² (40.3 m²)

- Empty weight: 2,360 lb (1,014 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 3,790 lb (1,723 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Armstrong Siddeley Puma piston engine, 230 hp (172 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 98 knots (113 mph, 182 km/h)

- Service ceiling 15,500 ft (4730 m)

- Endurance: 4½ hours

Armament

- Forward firing Vickers machine gun

- 1 or 2 Rear Lewis guns on scarff ring

- Up to 460 lb (209 kg) bombs

References

- Bruce 2 April 1956, p.387.

- Jackson 1987, p.97.

- Jackson 1987, p.100.

- Mason 1994, p.84.

- Bruce 13 April 1956, p.424.

- Mason 1994, p.86.

- Jackson 1987, p.102.

- Jackson 1973, p.50-52.

- Jackson 1973, p.56.

- Barnes 1976, p.211-213.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C.H. Handley Page Aircraft since 1907. London:Putnam, 1976. ISBN 0 370 00030 7.

- Bruce, J.M. “The De Havilland D.H.9: Historic Military Aircraft: No. 12, Part I”. Flight, 6 April 1956. Pages 385—388, 392.

- Bruce, J.M. “The De Havilland D.H.9: Historic Military Aircraft: No. 12, Part II”. Flight, 13 April 1956. Pages 422—426.

- Gerdessen, F. “Estonian Air Power 1918 – 1945”. Air Enthusiast No 18, April – July 1982. Pages 61-76. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Jackson, A.J. British Civil Aircraft since 1919 Volume 2. London:Putnam, Second edition 1973. ISBN 0 370 10010 7.

- Jackson, A.J. De Havilland Aircraft since 1909. London: Putnam, Third edition 1987. ISBN 0 85177 802 X.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber Since 1914. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. Bombers of the 20th Century. London: Airlife Publishing Ltd., 2003. ISBN 1-84037-386-5.