Newsletter

Get the latest from Weapons and Warfare right to your inbox.

Follow Us

Explore

Small Arms

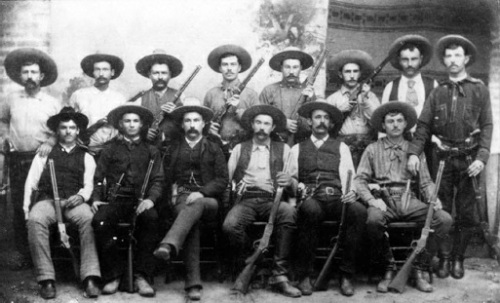

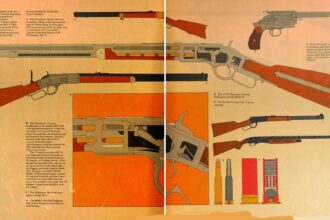

Winchester Model 1873

These Texas Rangers show off their Winchester Model 1873 rifles circa mid-1880s. This old print shows a cross-section of the Model 1873. The Gun That Won the West Produced: 1873–1919, 2013–Present (Winchester); 1991–Present (reproductions) The story of the Winchester 1873 rifle really began in 1860 with the Henry, a rifle that provided extreme firepower at a time when single-shot muzzle-loading…

Most Recent

THE MAGAZINE RIFLE II

General Crozier, as he had instantly become, had a very senior backer. This was President Teddy Roosevelt, who had succeeded President William McKinley after the latter’s assassination in September 1901. So on 7 April 1902 Crozier authorized the first production of the new Springfield 1901 rifles. By 16 February 1903…

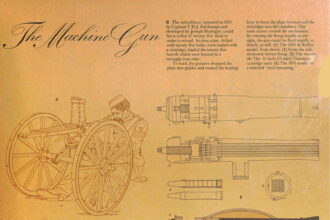

The Industrial Revolution and Machine-Gun Prototypes

The fundamental changes, including manufacturing and financial practices, that came about during the Industrial Revolution greatly speeded machine-gun development. The first patent using the term “machine gun” was issued in the United States in 1829 to Samuel L. Farries of Middletown, Ohio. This grant seems to imply that the term…

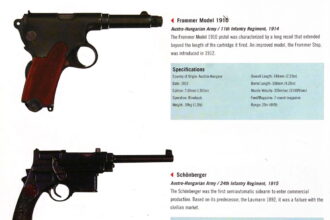

WWI Austro-Hungarian Small Arms Part I

Roth-Steyr Models 1907 and 1912 Austria-Hungary finally moved to replace its aging Rast-Gasser revolvers with the Roth-Steyr 8mm Pistol Model 1907 and the 9mm Steyr Pistol Model 1912. Österreichische Waffenfabrik Gesellschaft (Steyr) manufactured some 60,000 Model 1907s; Fegyvergyr of Budapest produced another 30,000. The Model 1907, or Repetier Pistole M.…

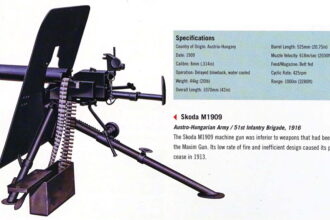

WWI Austro-Hungarian Small Arms Part II

Machine Guns Maxim traveled Europe while demonstrating his weapon. He was accompanied by Albert Vickers, a steel producer from South Kensington who had become intensely interested in Maxim and his invention. In 1887, Maxim took one of his guns to Switzerland for a competition with the Gatling, the Gardner, and…

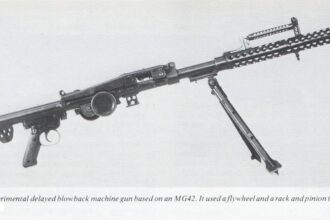

Barnitzke Machine Gun (Flywheel delayed blowback)

7.92x57mm cartridge 1945 The German Gustloff Barnitzke light machine gun. Derived from the MG 42 by Karl Barnitzke, the weapon used an unusual delayed blowback action consisting of two flywheels in a rack and pinion arrangement. The flywheels were exposed to dust and mud, and were overcomplicated in design, and…

Machine Guns WWI: Issue, organization and doctrine

The German MG08, fitted with an optical sight and an armoured cover for its water-jacket. A graphic representation of machine gun cones of fire and beaten zones. Taken from British machine gun training notes. The level of machine gun issue in the armies of the major powers in 1914 was…

Most Popular

WWI Austro-Hungarian Small Arms Part I

Roth-Steyr Models 1907 and 1912 Austria-Hungary finally moved to replace its aging Rast-Gasser revolvers with…

Antimaterial Rifle

South African DENEL 20X110HS NTW-20 Rifle procured for evaluation in the United States The antimaterial…

Barnitzke Machine Gun (Flywheel delayed blowback)

7.92x57mm cartridge 1945 The German Gustloff Barnitzke light machine gun. Derived from the MG 42…

Volkssturm Small Arms

Primitiv-Waffen-Programm As a last-ditch measure in the nearly lost war, on 18 October 1944 the…