Newsletter

Get the latest from Weapons and Warfare right to your inbox.

Follow Us

Explore

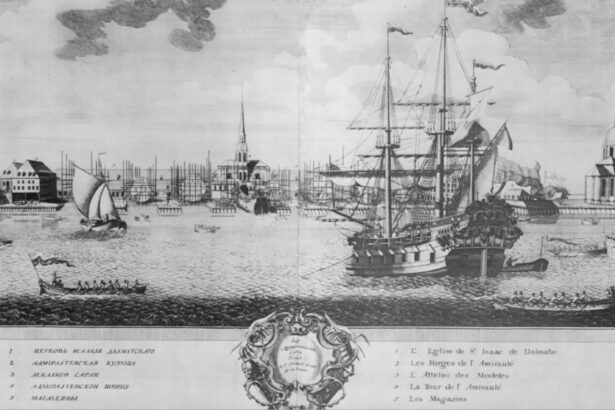

Imperial Russian Baltic fleet shipyards

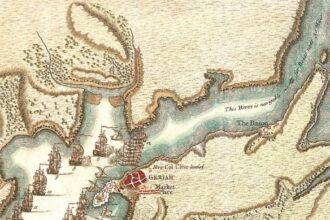

A representation of St Petersburg in 1716 by the contemporary architect Marcelius (no first initial available), showing the administrative and logistical hub of the Baltic fleet in its early years. The view is taken from the banks of the Neva looking across towards the centre of the city, with an unidentified warship anchored to the right and various small craft…

Referenced by West Point, Wikipedia, Army University Press (army.mil), Library of Congress (loc.gov), Encyclopedia Britannica and more.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Weapons and Warfare right to your inbox.

Follow Us

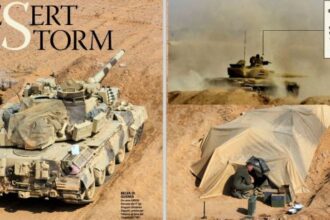

AMX-30B2 and the Gulf War 1991

The French participation in the Gulf War, codenamed Opération Daguet, saw the deployment of the 6e Division Légère Blindée (“6th…

ATTACK ON GHERIA, 1756

On 12 February 1756, a British naval squadron under Rear-Admiral Charles Watson demanded the surrender of Gheria, a stronghold on…

Seven Years’ Wars – Political Overview

Count Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz (1711-1794) The idea of an Austrian alliance with France had been first outlined by Count…

Most Recent

George Washington and The American Revolution War “Grand Strategy”

The entire goal of the American Revolution including the penning of the Declaration of Independence was to gain the colonists and the newly formed American nation legitimacy internationally. The Declaration of Independence was written to…

Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Test High Energy Asset (ATHENA) laser weapon system

In the realm of modern warfare, where technology evolves at breakneck speed, traditional defense mechanisms are often rendered obsolete against emerging threats. Among these threats, unmanned aerial systems (UAS) have become increasingly prevalent, posing significant…

Save posts, accessibility and store

Weapons and Warfare has been updated with a save posts feature, accessibility options and a new store. While on a post page, you can now easily save a post to read later: New accessibility options…

Popular Categories

Random Reads

TO KILL A MAN

Abbeville Boys by Robert Taylor. Adolf Gallands Fighter Wing JG-26 (Me109s) taking off to do combat with R.A.F. Spitfires and…

1944-45 WWII in Czech State and Slovakia

The Nazi puppet state in Slovakia sent small ground and air units to fight against the Soviet Union. Formerly a…

Soldier and Warrior

Soldiers are warriors who fight for pay and, as such, are comparative latecomers to the field of human conflict. The…

Battle of Abu Klea

The Battle of Abu Klea by William Barnes Wollen (January 16-18, 1885) The fierce Battle of Abu Klea was fought…

More Stories

“Potsdamer Riesengarde”

The Potsdam Giants was the Prussian infantry regiment No 6, composed of taller-than-average soldiers. The regiment was founded in 1675 and dissolved in 1806 after the Prussian defeat against Napoleon. Throughout the reign of the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia (1688–1740) the unit was known as the “Potsdamer…

Russian Army 1915 Part II

Russia lacked officers, and lacked still more N.C.O.s who could link them with the men. The gap between the Russia of the officer-class and the Russia of the private soldiers widened throughout 1915. ‘The officers have lost all faith in their men’, wrote a well-informed staff captain in autumn, 1915.…

The Armada – Failure Guaranteed?

Elizabeth I and the Spanish Armada; the Apothecaries painting, sometimes attributed to Nicholas Hilliard. A stylised depiction of key elements of the Armada story: the alarm beacons, Queen Elizabeth at Tilbury, and the sea battle at Gravelines. Strategically, the determination of Spain’s Philip II to destroy his chief Protestant and…

Fall of Nanjing II

Zeng Guoquan had a dream. He dreamed that he was climbing up a high mountain peak, all the way to the summit. When he got to the top, however, he couldn’t find any path to continue forward, so he turned around. But when he did, he saw that there was…

Home Defence Mid-July 1940 Part I

Both Germany and Britain were hindered by their lack of military or political intelligence throughout the summer of 1940. A central explanation for Hitler’s ill-judged speech at the Reichstag was that the Germans had no inside knowledge of the British political scene, and were still relying on the preconceived notion…

“Floating Chrysanthemums”

USS BUNKER HILL hit by two Kamikazes in 30 seconds on 11 May 1945 off Kyushu. Dead – 372. Wounded – 264. (Navy) Map showing approximate radar picket positions, radar ranges, and initial Japanese plane sightings. May 4, 1945 In Japan the chrysanthemum is probably the most beloved of all…

Northern Ireland

An unexpected revival in the commitment to home defense was seen not in the shape of the defense of Britain from invasion, the key issue in 1940, but rather that of dealing with sustained civil unrest in Northern Ireland. Much of the army served there from 1969, and, in terms…

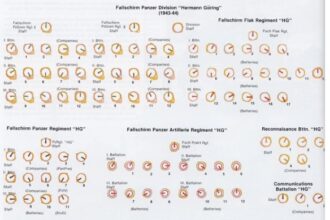

‘Hermann Göring’ in the Mediterranean.

Sicily 1943 Operation ‘Husky’, the Allied invasion of Sicily, commenced on 10 July 1943. Surrounded by Italian units, most of which were of third line quality and only too happy to surrender, the ‘HG’ Division and the Army’s 15. Panzergrenadier-Division fought well, despite coming under devastating fire from Allied naval…

Most Popular

AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT IN BRITTANY, 1758

British coastal assault on St Cast in Brittany in September 1758. A German map, published…

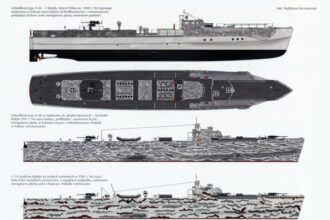

German Schnellboot (S-boat)

Schnellboot S-80 torpedo boat Camo Operations with the Kriegsmarine S-boats were often used to patrol…

Lend-Lease to the USSR

American Lend-Lease supplies to the USSR 1941–45. Soviet historiography is mocked in the West, where…