The Incan military was highly organized and consisted of nearly 200,000 soldiers. The military served as a public service organization that brought food and materials from one region of the country to another and trained specialists who contributed to the growth of the empire. In order to prepare future soldiers, military training took place on a bimonthly basis and began with boys as young as ten years old, who took part in physical activities such as wrestling, weight lifting, and sling shooting. This training enabled the Incan commanders to determine which soldiers could be used as specialists, such as builders, stonemasons, bridge experts, and assault leaders. Village elders reported on the progress of the boys, whom the military drafted as either warriors, carriers, or craftsmen. Short-term service drafting ensured an ample supply of young men in each district. The periods of service depended upon climatic conditions, and not all men returned to civilian life. The commanders ordered the most outstanding soldiers, those who were the bravest, the most disciplined, and the most adept at fighting, to remain permanently in the military.

The organization of the army was similar to that of the decimal system utilized by the Romans. Although the commanders were usually members of the Incan royal family, many ascended from the ranks because of their extraordinary ability and devotion to the emperor. One of the demands placed upon the commanders, who had to deal with the logistical problems of the roads and supplies, was to calculate the most efficient way to move their military across the country. Because the strategy was to fight only if absolutely necessary, the commanders had to ensure a deployment of soldiers superior to that of the enemy and would not waste manpower by sending too many. On important occasions, the emperor personally assumed command of a campaign. Topa Inca Yupanqui, for example, took personal command of an effort to expand the empire by overseeing the extension of the main highways, a task too difficult for an army commander to handle alone. Soldiers were required to participate in battles as far away from their homes as possible in order to avoid fraternization and to allow them to experience the vastness of the country and the grandeur of the empire. Because the purpose of the military was both to defend and to extend Tahuantinsuyu and to serve the Sun God, individual glory in battle was not valued by the Incas.

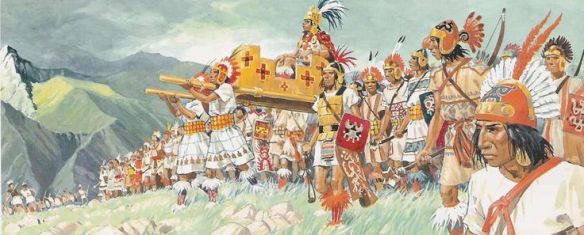

Weapons, Uniforms, and Armor

The Incas had an advanced Bronze Age technology in the fifteenth century that served as the foundation of the military force. The sling was the deadliest projectile weapon. Other effective weapons included bows and arrows, lances, darts, a short variation of a sword, battle-axes, spears, and arrows tipped with copper or bone. The weapons used by the Incan lords were decorated with gold or silver. For protection military leaders wore casques, or helmets, made from wood or the skins of wild animals and decorated with precious stones and the feathers of tropical birds. Soldiers wore the costume of the province from which they came; their armor consisted of a wooden helmet covered with bronze; a long, quilted tunic; and a quilted shield. The soldiers, who jogged at a pace of about 3 miles per hour and traveled nearly 20 miles per day, carried only their own supplies, while an army of soldiers was responsible for carrying baggage on their backs. Garrisons were housed in fortresses, whereas detachments occupied storehouses, which consisted of magazines filled with weapons, grain, and ammunition. Sacsahuaman, the site where the Incas defeated the Chancas, was the only fortress garrisoned by the Inca people. Sacsahuaman was only one of many Incan fortresses; others included Paramonga, a fortress constructed like a mountain of adobe bricks that had once been a part of the Chimu kingdom. These storehouses provided the army with food and clothing, thus avoiding the necessity to pillage villages as the army traveled across the country.